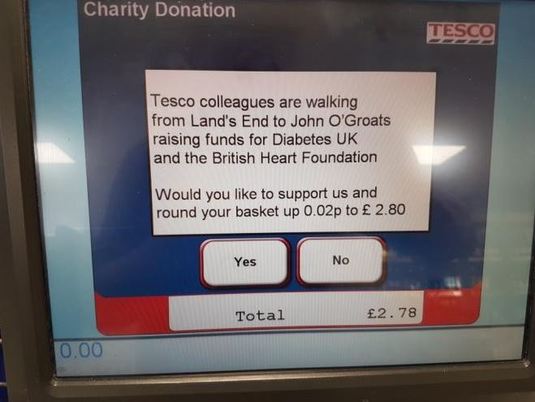

Public frustration with charities and fundraising had been building for some time... Public frustration with charities and fundraising had been building for some time... It’s tempting to think that the recent fundraising crisis came out of nowhere – that public resentment was just whipped up by the media and a few horror stories – but the reality is different. Frustration and dissatisfaction had actually been simmering away for a long time. In 2016, nfpSynergy reported that the charity sector had one of the lowest complaint rates across seven sectors, but the highest level of people wanting to complain but not doing so. Given that the other sectors included pensions, mortgages and broadband providers, that’s a sobering statistic. So why have people been growing increasingly unhappy with charities? Specific cases of bad practice haven’t helped, but I think there’s a broader issue. Most of our public fundraising methods seem to rely on interrupting – rather than complementing – our everyday lives. We get stopped in the street. People knock on our doors. Charity appeals pop up on TV and through our letterboxes. In a world marred by spending cuts and growing inequality, this may feel inevitable. More and more people are being denied happy and healthy lives, and charities are stepping in to pick up the slack. Desperate times call for desperate measures, and if these fundraising methods work and people have the money to donate, what’s the problem? Unfortunately, many fundraising methods seem incompatible with a changing society. Digital technology has given people an unprecedented level of choice and flexibility. We stream music that we want to listen to, instead of sitting through songs we don’t like on the radio. We watch our favourite programmes on catch up TV, rather than 'seeing what’s on'. We increasingly live in our own bubble where we do things on our own terms. So when we perceive that we’re being interrupted unnecessarily – whether by a company, a charity or an individual – we often feel harassed or angry. So street, door-to-door and television fundraising – while hugely successful financially, particularly for household name charities – are often negative experiences for the public, stirring up feelings of pressure and guilt. I’m not saying that 'traditional' forms of fundraising are fundamentally wrong, or that negative media coverage is always justified. However, in these tough times, many charities need to raise increasing amounts from the public to keep supporting their beneficiaries. For this to be sustainable, we need to be more creative and varied in our fundraising efforts. A popular buzzword today is ‘disruption’ – the concept (originating in Silicon Valley) of smaller companies unseating market leaders in an industry with an innovative or simpler solution. But when it comes to fundraising, perhaps the most effective form of ‘disruption' is actually to be as non-disruptive as possible. We need to find more ways to fundraise that fit in with or add value to people’s lives, rather than interrupting them. I’ve seen a few great examples recently – and while many are being implemented by large charities, there’s plenty that the whole sector can learn: 1. Rounding up in shops Recently, staff in my local Tesco in Bristol were fundraising for Diabetes UK and the British Heart Foundation. To support their efforts, Tesco added a prompt to their self-service machines asking customers to make a small donation to round up their bills: Over about a month, I must have donated ten times (I’m not a very strategic shopper, and Tesco is a one-minute walk around the corner). Never more than 10p – but with so many customers and transactions, you can imagine how this small but frequent giving can add up. While this did involve adding an extra screen to the self-service process, I could choose to donate or decline within two seconds. It didn’t feel obtrusive at all, and there was no awkwardness in saying no. Many people will have supported two charities that they might not have thought of giving to before. Smaller charities may find it near-impossible to forge a partnership with a major supermarket. However that doesn’t stop you approaching local shops or restaurants about a similar arrangement, or applying to supermarket community schemes like Waitrose’s green token scheme. You can also look at joining nationwide schemes like Pennies. 2. Good old-fashioned community fundraising Community fundraising is brilliant because it performs a social function as well as raising money. It's something positive to do and provides an opportunity to meet new people, which can be really important for some. While most people immediately think of the Macmillan Coffee Morning – which raises almost £30million annually – personally I love Mind’s Crafternoon fundraiser. This promotes mental health and mindfulness, while encouraging people to come together and focus on making something. Any charity – no matter what size – can design an attractive community fundraising idea for their own supporters, whether that means a database of a thousand people or a small group of friends and family. The key is to develop your idea in consultation with your target audience, start small, gather feedback and gradually scale it up. Ultimately, community fundraising works best when it's led by volunteers, with minimal input and support from paid staff. 3. Social media collaboration Building an audience for fundraising is tough for smaller charities, so getting a leg-up makes a huge difference. I’ve always loved this example of how the popular Humans of New York photoblog raised over $100,000 in less than an hour, by combining a powerful ask for a local cause with an inspiring story. Founder Brandon Stanton had already built a huge audience that enjoyed glimpsing other people’s lives and hearing their stories, so appealing for help was a logical next step. Winning the trust of an audience that are already passionate about something, and making a related ask on the platform they already use, is another great way of weaving fundraising into the fabric of everyday life. Building a relationship with - for example - a blogger or YouTube star isn’t easy, but might be a better bet than approaching major companies, particularly if there’s a reason why they’d support your cause. Try looking out for rising stars and make contact with them before they hit the big time. 4. Gamification Ever been through Stockholm Airport and seen these charity arcade machines? I love this for two reasons. Firstly, it takes something that’s already popular and adds a fundraising twist. If people like arcade machines in airports, why wouldn’t they love using them for a good cause? Secondly, this is a brilliant example of the gamification of fundraising. This increasing trend uses games, challenges and adventures to give people an added incentive to support a cause – and it really works. You’ll probably struggle to get arcade machines placed in major airports. However, you can still use this as inspiration: can you ‘gamify’ any of your existing fundraising efforts, or add a fundraising twist to something your local supporters already enjoy doing? 5. Making donating easy When people decide they want to donate to you – no matter how or where – it’s not the end of the story. The physical act of donating has to be intuitive and convenient – if it’s too complicated, you’ll lose donors. As technology moves on, people expect the organisations they interact with to keep pace. The use of contactless cards is booming – contactless payments now account for a third of all card purchases, up from 10% just two years ago. Cash is a fading force, and charities are losing out by still relying too much on it – by as much as £80million per year, according to this report. It’s worth exploring options now for taking card and contactless payments, as the cost and barriers to entry will continue to come down for smaller charities. Also, make sure your donation and registration forms (both online and paper) are as simple as possible. This blog is based on a version that was first published on Localgiving in January 2018. If you've enjoyed reading it, please sign up to our mailing list for more blogs and advice.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Like this blog? If so then please...

Categories

All

Archive

May 2024

|

Lime Green Consulting is the trading name of Lime Green Consulting & Training Ltd (registered company number 12056332)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed