|

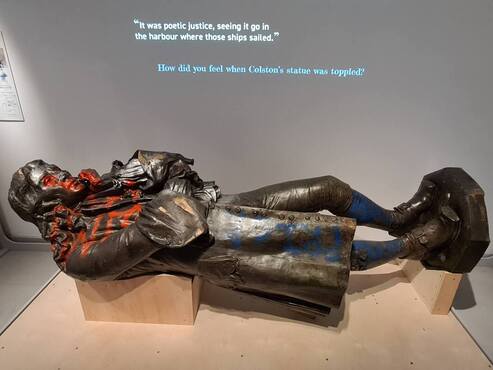

It’s been nearly five years since we first shared some tips on creating an ethical fundraising policy, and 2-3 years since we really embraced the complex debate about problematic philanthropy. To kick off 2023 on a thoughtful note, this new blog brings together those ideas - and some new ones - for anyone looking to create an ethical fundraising policy. Problematic philanthropy - not as clear-cut as it seemsSummer 2020: the statue of Edward Colston makes its journey from high-profile city-centre plinth to horizontal resting place in a Bristol museum, via a swim in the River Avon. The charity sector is awash with talk about the issues with accepting grants and donations linked to historical figures involved in the slave trade. There’s a clear view – philanthropy can’t be used to excuse or whitewash the injustice of how wealth was first made. Spring 2019: the Sackler Trust halts grantgiving in the wake of the Purdue Pharma scandal. The US pharmaceutical company, closely linked to the Trust, is accused of fuelling the US opioid crisis that killed almost half a million people, having spent years aggressively pursuing legal action so they could continue selling their highly addictive drugs. Slowly, UK cultural institutions like the British Museum and the National Portrait Gallery begin distancing themselves from the Sackler name. Clear-cut cases like this make us all understand the need to swerve “bad money”, and make the process of writing an ethical fundraising policy seem pretty straightforward. Except that (mixed metaphor alert) once you open this can of worms, you get hit by about a million grey areas. Consider the following examples: Despite the Colston backlash, there are plenty of other links between the slave trade and the charity / arts sector hiding in plain sight. Here in Bristol, the Society of Merchant Venturers continue to donate £250,000 per year to local causes. In London, the Tate Galleries continue to take their name from Henry Tate, whose Tate & Lyle sugar company was fundamentally connected to the slave trade. Many UK charities happily receive small-scale income via the Amazon Smile programme, despite Amazon being associated with a raft of harmful practices including “extreme tax avoidance, poor working conditions in factories, slave labour in their supply chain, and catastrophic environmental impact” (source: FRIDA). And how many charities have received grants from household name corporate foundations like the Lloyds Bank Foundation, Santander Foundation and the RBS Skills & Opportunities Fund? Yet consider this quote from a 2018 report by Ethical Consumer magazine: “The UK's big five high street banks [Barclays, HSBC, Lloyds, RBS and Santander] are hindering the sector's efforts to tackle climate change by continuing to profit from some of the world's dirtiest fossil fuel projects. [...] The UK's mainstream banking industry has involvement with virtually every ethical ‘problem sector’ from factory farming through to nuclear weapons.” The case against philanthropy - and the dilemma for charities and social enterprisesNone of this is about passing moral judgement on the specific names above, merely to demonstrate how much more complicated things are than Edward Colston and the Sackler Trust. An uncomfortably high number of philanthropists and foundations have clear links with the slave trade, climate damage, tax avoidance and damaging employment practices - all of which actively harm the very people many charities exist to help. As we argued in 2020, philanthropy buys a seat at the table for a very specific audience - wealthy, privileged, usually white and male. Through their decisions on what they do/don't fund, their roles on Boards and advisory groups, and their status as thought leaders, they gain disproportionate influence in implementing their own vision of equality, social change and climate justice - a vision that is probably very different from your own. This gives rise to some important questions about what criteria should you apply when evaluating donations:

Given this moral and philosophical minefield, how do you go about creating an ethical fundraising policy?Firstly, here’s how not to do it… Don’t go out and find a template ethical fundraising policy, copy and paste in some organisational details, and tick it off your to do list. As is usually the case, an honest, thoughtful discussion is a prerequisite to any good policy or strategy. Don’t base your decisions on the sum total of people’s personal beliefs, what you’ve seen other organisations do in the past, or what the loudest voices are saying (whether that's your senior leadership, trustees or existing donors). And don’t over-react to any specific recent event in the media. If you do, you’ll be basing your decisions on the wrong criteria, oversimplifying complex issues, and setting yourself up for trouble. You may later find yourself facing pressure to turn away a donation that technically contravenes your policy in an unexpected way, or facing criticism for accepting a donation that has implications you hadn't considered. The first step is to organise a structured discussion or workshop, involving people at all levels of the organisation. Start by explaining the context, giving some examples of problematic donations to consider, and outlining the risks of getting your policy wrong. Feel free to share this blog with everyone in advance. The vital context for any good ethical fundraising policy is YOUR specific work and mission. You should look to identify types of donor or donation that might:

As a general rule, if this discussion is quick and easy, and everyone is readily in agreement, you probably haven’t given it enough thought! You should aim to arrive at a list of criteria for donations that you’d definitely reject, and donations that would prompt additional action, for example further research into the source of someone’s wealth, an in-depth discussion with your trustees, or a consultation process with your service users. Once you’ve made some headline ethical decisions, you still need to decide how to implement your policyFor example, you’re likely to need a due diligence process for gifts over a certain value, guidelines for approaching vulnerable donors, and an ethical checklist for any new third parties or suppliers. To decide what specific processes and guidelines you need, you should carefully map out all the types of fundraising your organisation does, and the potential ethical risks with each. You also need to support fundraising staff who are at the frontline of putting your policy into action. They need a safe space to be able to raise and discuss any ethical concerns, and a complaints process if they feel the organisation is breaking its own policy. And they need a fundraising culture that isn’t simply about results at all costs. A good ethical fundraising policy is quickly compromised by demanding or unrealistic fundraising targets that encourage people to forget any concerns and just pursue the cash. Training and workshop facilitationHonestly, this blog could have been twice as long. There are countless other examples and considerations I could have included, but I hope this is a helpful starting point. While creating an ethical fundraising policy can be complicated, but it’s a really empowering and important thing to get right.

To explore things further, we run periodic talks and Q&A sessions on ethical fundraising and problematic philanthropy - check out our training page for more information. And we've also facilitated ethical fundraising workshops for organisations, focused on both challenging debate and concrete decisions. Get in touch if you'd like to explore how we could run one with you.

1 Comment

|

Like this blog? If so then please...

Categories

All

Archive

May 2024

|

Lime Green Consulting is the trading name of Lime Green Consulting & Training Ltd (registered company number 12056332)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed