|

There's plenty to worry about at the moment - in fundraising and in society. With every passing crisis, charities and social enterprises face increasing need, but more financial pressure - and it’s no different now with rising inflation and the cost of living crisis.

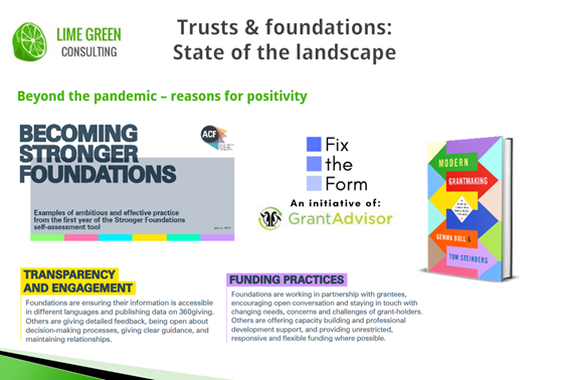

On top of that, there’s much entrenched frustration directed at funders, whose grantmaking processes and policies add a further headache. Only last week, new research estimated that organisations spend £900million per year meeting the demands of applying to funders. Our own blog charts this rising frustration. We've written almost enough rants to fill a small book, whether about the human cost of bad application processes, the need for funders to turn over a new leaf, the injustice of the lack of infrastructure core funding, or the general frustrating things that funders say. While it feels important to be honest and realistic about these challenges, it's also nice to focus on positivity where we can find it. And it's true that the pandemic has prompted some positive reflection and reform from many progressive funders. When updating our training content recently, I really enjoyed preparing this slide highlighting some of the current movements and reports on grantmaking that give us reasons to be optimistic. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that it’s also one of our most colourful slides:

On the right of this slide is a book that I’ve been promising to review for months, because it gives a glimpse of a possible future for grantmaking that is better for everyone - more accessible, more respectful, more even-handed, and more impactful as a result.

Modern Grantmaking is written by Gemma Bull and Tom Steinberg. Both have worked for funders and been responsible for giving away money - a job that many people, particularly those outside the sector, might think sounds enjoyable and straightforward, but is actually fraught with challenges. Both have evidently experienced the creeping unease and frustration that comes with the territory of seeing money given away badly. So they sat down and spoke to countless experts about what the common issues are, and what good grantmaking should look like – and Modern Grantmaking is the result. Obviously, this book isn't written for people like me who seek funding, but for those on the other side of the fence who give money away and want to do it better. But for fundraisers, there's plenty of useful insight - and reassurance - in understanding more about the issues that grantmakers are wrestling with. The first reason for positivity is simply that a modern grantmaking movement exists. That a growing number of people in influential positions are talking and writing about how grantmaking isn’t good enough, and how it can be better. Early on, the authors write that in the last decade, such ideas are “growing up like green shoots through cracks in a pavement. These shoots are now so numerous and so vigorous that the paving slabs of traditional grantmaking practice are threatening to buckle.” Yet I wonder how many of these reformist ideas actually make it far beyond a tight circle of people. Certainly, the vast majority of fundraisers who come on our training courses and share frustrations about the things funders say and do, show little sense of this buckling pavement under their feet. So to have a new book that brings together these ideas, shouts about the need for reform, and signposts people towards a number of growing modern grantmaking movements, is a beacon of hope for fundraisers in a difficult landscape. As well as influencing funders, this helps to legitimise the frustrations that fundraisers feel, and galvanise them to find small ways to challenge and push back. If more of us are talking the same language, change happens faster. Last week, I saw a small but significant example of this on Twitter:

Modern Grantmaking gave me a telling glimpse into the curious career of a grantmaker - one with few structured development opportunities, and little incentive to do things differently. In the authors’ words, "grantmaking can also be an ideal career for people who just want a quiet life and a reliable salary.” Firstly, grantmaking comes across as at best a very young profession, and arguably not a recognised profession at all. The authors explain how there's no established career path into grantmaking, very little tailored training to help with the key skills required, and no accreditations or recognised standards to measure performance against. Secondly, there’s not much accountability. In a world without enough funding to go around, if a funder treats you badly, where are you supposed to take your ‘business’ instead? Can you afford to complain? If funders don’t recognise themselves as needing to provide a service to grantseekers, they won’t measure themselves in those terms. Reading this, suddenly many of my past experiences with funders made sense. Seeking funding is a lot like being a UK rail passenger - you might not enjoy the experience, it might feel unpleasant and at times dehumanising, but good luck finding an alternative. Now imagine the added fear that if you complain about the delays and overcrowding, they might simply stop offering you a seat at all.

It's cathartic to read this insight in Modern Grantmaking, and I'd recommend you do so yourself. But the best thing about the book is how it creates an alternative vision for grantmaking, as a profession with the service mentality, the standards and development opportunities, and the pressure to be better.

There's advice about how to recognise and manage the power and privilege that you have as a grantmaker. How to convince colleagues that you may not have the right perspective and lived experience in the room to evaluate funding proposals and make fair decisions. How easy it can be to strong-arm a charity into completely changing their project or budget, because of a seemingly innocuous suggestion you make. There are whole chapters dedicated to improving how you treat applicants, even if nobody is demanding it. How to understand what the experience is like for grantseekers trying to navigate your website, fill in your application form and go through the agonising wait for a decision - then take steps to improve that experience. A recurring theme is the importance for humility - just because you have all the money, it doesn’t mean you have all the knowledge. For grantmakers with this mindset, the book contains practical advice on how to commission independent research to understand a social issue well enough to judge funding proposals, and how to start reading evaluation reports with a critical eye that genuinely broadens your understanding, rather than just looking for quick evidence that your grants are working.

Reading all this was music to my ears as a fundraiser. And what makes Modern Grantmaking so convincing is that it’s peppered with horror stories of grantmaking done badly, and inspiring case studies showing how funders have reaped the benefits of making positive changes.

The book also has a real grassroots feel. While it may be picked up by the occasional Chief Executive of a funder, it's really written for those people whose day-to-day work has the power to make grantseeking a good or a miserable experience – the people who design application forms, respond to emails and answer the phones. Of course, we can hope that these people will still influence those working above them, and will ultimately go on to lead trusts and foundations in the future, and set a new standard for grantmaking. I hope that any grantmaker wanting to genuinely maximise their social impact will read Modern Grantmaking, then do what they can to push through change. I guess that will be the ultimate measure of the book’s success. But, in the meantime, if you’re a frustrated bid writer wondering if, how and when things will ever be done better, I’d also recommend getting yourself a copy - you’ll be able to take plenty of ideas and much-needed hope from it. You can buy your copy of Modern Grantmaking, and read more about the movement and the authors, by clicking here.

0 Comments

|

Like this blog? If so then please...

Categories

All

Archive

May 2024

|

Lime Green Consulting is the trading name of Lime Green Consulting & Training Ltd (registered company number 12056332)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed