|

We published this blog in June 2020, 11 days after the statue of Edward Colston was brought down. It's now several years on, and not enough has changed...

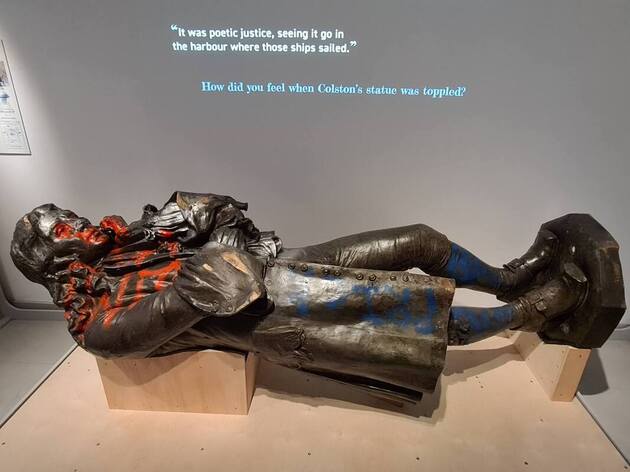

Time will tell, but I really hope the last couple of weeks will be a landmark moment in history, with the Black Lives Matter movement gathering widespread support, and people doing some genuine, long-overdue soul-searching about racial inequality. Bristol, where I live, has felt like the epicentre of grassroots change, with the dramatic toppling of the statue of Edward Colston. Bristol is a city haunted by the slave trade, and this statue has been a focal point of the long debate about the legacy of Edward Colston. It's important to remember that the statue is very much the tip of the iceberg – at last count, Bristol ‘boasts’ eight streets, two pubs, two schools, a fruity bun and the city’s largest music venue named after Colston. Disentangling the messy web spun by such a prolific philanthropist has proved complicated, particularly as change has long been opposed by influential philanthropists in Bristol. People only took matters into their own hands after many tried - unsuccessfully - to find a democratic solution for years. This is something to be celebrated - and many have been, including the CEO of the Wolfson Foundation:

I want to agree with this sentiment, but actually I think we're at the very beginning of the argument, not the end. While few people would actively argue that philanthropy excuses the unethical practices that first generated that money, this view is inadvertently endorsed every day - and fundraisers and charities are very much complicit in this. There are examples everywhere, once you start to look.

The day after the statue came down, I felt this strange need to go down to the site myself, and just...think. I started writing this blog down there. Looming above the smashed plinth and handful of people still milling about was Colston Tower - a building that can’t be torn down by people who are fed up of waiting for official action. If Bristol wants to fully rid itself of the Colston legacy, this is going to take a conscious decision from those in power whose track record - no matter they say - still suggests they believe that philanthropic good deeds outweigh harmful past actions.

Of course, this isn't just a Bristol problem. London's Tate Galleries take their name from Henry Tate, whose company Tate & Lyle was inextricably tied with the sugar industry and the slave trade.

A great many museums have received large donations from the Sackler Trust, and some bear the Sackler name. You might well know that the Sackler Trust was closely linked to Purdue Pharma, who are accused of fuelling the US opioid crisis and spent years aggressively pursuing legal action so they could continue selling their highly addictive drugs. But we're on safer ground with most corporate foundations, right? I know countless grassroots community projects that have benefitted from grants connected to the banking sector - think Santander Foundation, the RBS Skills and Opportunities Fund, and Barclays' new 100x100 UK COVID-19 Community Relief Programme. Yet a 2018 report by Ethical Consumer magazine said this:

How many charities write ethical fundraising policies that prohibit donations from philanthropists involved in these 'problem sectors', but wouldn’t think twice about applying for a grant from a foundation connected to one of the big five banks?

The trouble is that while most people have clear views about Edward Colston, underneath this there's a huge grey area. And the more you dig, the greyer it gets.

Many social welfare charities are funded by wealthy family trusts whose trustees have, for decades, both implemented and supported policies that drive a coach and horses through social mobility. Their businesses often pay as little tax as possible and profit greatly from things like zero hours contracts - which keep vast numbers of people, including so many charity service users, locked in poverty. 2020 brought a new entrant to the UK trusts and foundations scene: the Hargreaves Foundation – founded by Peter Hargreaves, major donor to the Leave.EU Brexit campaign, friend of Jacob Rees-Mogg, and a man who outlined his employment policies and interest in charities in an interview with The Sunday Times:

And I recently discovered this remarkable exclusion from a small family trust in Oxfordshire: “We will not support charities that in our view are ambivalent about, or actively campaign for the abolition of, field sports.” Imagine being so vehemently pro-field sports that you simply wouldn’t consider funding a charity that has even mixed feelings about fox-hunting?!

Does any of this really matter? Where should we draw the line? Should we only reject money from those who have been publicly condemned for doing Very Bad Things? Or are harmful but widespread business practices up for scrutiny too? When should we take people's publicly held opinions into account - when they actively harm our beneficiaries, when they go against our charity's message, or when we just find them personally repugnant? I'm not saying everyone will take issue will all of the above examples - or that you should. But it's an important conversation to have. And I think that recent events in Bristol should mark the beginning of the argument about hypocritical philanthropy, not the end. It's an inescapable fact that philanthropy is closely tied with extreme wealth, and most of that wealth is derived from activities that increase inequality. Philanthropy often buys people 'a seat at the table', and this gives a particular audience – wealthy, privileged, mostly white, usually male – disproportionate influence to implement their own vision of equality, social mobility and climate change. A vision that is, almost certainly, very different from your own. If we want to address this, we’re going to have to start digging a lot deeper than Edward Colston.

3 Comments

|

Like this blog? If so then please...

Categories

All

Archive

May 2024

|

Lime Green Consulting is the trading name of Lime Green Consulting & Training Ltd (registered company number 12056332)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed