|

Many fundraisers and small charity leaders that I speak to are under pressure to close a significant funding gap or meet a daunting fundraising target this year. This feels natural, especially in the current climate. But it's also likely to be holding back your growth potential. What if I told you that raising less money this year might be the smartest thing your organisation could do? When we're under pressure to raise funds quickly, we turn to tried-and-tested tactics. Such as writing a few more funding applications. Or searching for opportunities to secure another local authority contract. These tactics, when successful, give trustees and management a sense of security and progress - an extra zero on a financial report, a new project launched, a new staff member recruited. But how much security and progress does this really bring? By the following year, you're back in the same position, needing to close the same funding gap to avoid scaling back. Running to stand still. Having to work just as hard to raise the same amount, if not harder given the ever-increasing competition for funding. No breathing room or flexibility to respond to unexpected events or costs. It doesn't always have to be like this. Some income streams offer you the prospect of a higher return on investment, more flexibility and more security further down the line, if you take action now and can get that far. When we’re working with a charity or social enterprise on their fundraising strategy, we always encourage them to cast the net a bit wider and consider the potential of other income streams that aren’t immediately on their radar. Two income streams in particular. Regular giving and legacy fundraising - what are the benefits?Regular giving can be tricky and slow to grow, and may require a culture change if you've only ever previously relied on grants. But long-term, the return on investment can be significant, and the benefits huge. It generates unrestricted income that you can spend as you wish. Also, dependable income: if you start a financial year with 100 direct debits, you can be pretty confident of broadly how much you’ll raise and when, which is great for cash flow and financial planning. Plus regular giving is a great springboard for other opportunities: people who donate regularly and are engaged in your work may shout about you to others, unlock corporate fundraising opportunities with their employer, or become future major donor or legacy prospects. Legacy fundraising, while similarly slow to develop, potentially has an enormous long-term return on investment, partly because there’s very little to actually spend money on - just a small up-front investment in some resources and strong messaging to drip-feed to your supporters via email, social media etc. A very small outlay may bring a game-changing windfall down the line. I’ll never forget visiting a family centre in Gloucestershire the day they’d been contacted by a solicitor to notify them of a forthcoming unrestricted donation of £150,000 - a former service user had sadly passed away and generously promised them a percentage of the proceeds of their house sale. A joyful moment and totally transformative for their future work. Given this potential, why don't more organisations take the plunge and invest in long-term income streams?Firstly, there are a couple of good reasons. Some organisations are fighting to keep their doors open in a thankless financial climate, and simply don’t have any possibility of waiting for a return a few years down the line. Others are operating in a disadvantaged local community where these income streams simply aren’t a good fit, because they have little or no opportunity to reach people with the ability to donate. However, other organisations have somewhat understandable, but much less justifiable, reasons for writing off these income streams:

This last point is a really crucial one. In trying to steer away from activities that risk not raising as much as hoped, many organisations steer into the greatest risk of all: becoming over-reliant on ‘safe’ income streams that gradually dry up over time, then hitting serious financial difficulties because it’s too late to react and try something new. I often use a plane analogy here. If you were flying a plane that you knew was steadily running out of fuel, the risk of attempting an emergency landing might feel daunting. In different circumstances, you wouldn’t dream of trying it. But the alternative option - carrying on flying and running out of fuel mid-air - is actually guaranteed to fail. So an emergency landing, while more drastic, is comparatively lower-risk. In conclusion - invest if you possibly canIt’s true that many organisations aren’t in a position to easily invest in high-potential, slow-burn activities like regular giving and legacy fundraising. But this isn't an issue with the income streams themselves. The problem might be that nobody took the plunge and invested in them ten years ago.

If your organisation does have a comfortable level of reserves, or can otherwise take action to create some breathing space, I’d strongly recommend exploring how you can diversify your fundraising activity and invest in long-term growth activities. In 5-10 years, you’ll likely be extremely grateful for it. Even if that means raising less money this year, it could be the best decision that you ever make.

1 Comment

It takes a lot of different things to ensure that fundraising is successful in an organisation: talented people, adequate budget, a convincing case for support and often a drop of good luck. But there’s something else that too often gets overlooked: organisational culture. During our training courses and strategic planning work, we talk a lot about the importance of having a whole-organisation approach to fundraising and a fundraising-friendly culture - but it can be difficult to explain what this really means. For me, a fundraising-friendly culture is when everyone in your organisation - whether that’s five, 50 or 500 people - recognises the importance of good fundraising to the bigger picture of your work, understands all the little things they can do to support your fundraising efforts, and feels motivated to play a part. So what are some of the features of a fundraising-friendly culture in a charity?This isn't an exhaustive list but, in my experience, the best fundraising organisations always:

🎉 Celebrate success - it’s a really tough time for fundraisers currently. We're burnt out, under pressure due to unhealthy levels of scarcity and competition, and we hear no a lot more than we hear yes - even when we're doing a good job. Added to that, people often seem to take more interest in our work when it’s underperforming, but simply move the spotlight to something else when it’s going well. So when that big grant success comes in or an event smashes expectations, shout about it internally – it’s quick, easy, free and makes a world of difference. 💭 Allow space for reflection - under pressure to deliver, fundraisers rush from activity to activity. It’s often straight onto the next thing in the diary or on the to-do list, leaving little or no time to reflect on what went well and how to improve things next time. Good fundraising organisations encourage their people to stop and think – and join in that process constructively – whether that’s through formal evaluation or just allowing a little room to breathe. The best planning and debriefing meetings raise more money indirectly than most activities! 🎯 Set sensible targets - there are a lot of negative associations with the word “targets”, but they can actually be very helpful in providing structure to staff, who may not otherwise know whether they’re doing a good job. However, targets need to be realistic, evidence-based and planned in collaboration with your fundraising team. If they’re imposed on people from above without any context or discussion, this breeds resentment and pressure. 👨👩👧👧 Involve and engage everyone in fundraising - your whole team (including staff, trustees and volunteers) have a role to play, but it’s important to reassure them that this doesn’t mean making the ask, shaking a tin, or doing anything that makes them feel uncomfortable. Instead, they can supercharge your fundraising by providing data, sharing updates, making introductions and contributing ideas - but they need to know this and feel encouraged to help. 💥 Strive to articulate human, person-centred impact - there's no getting away from the fact that funders and donors love to understand the impact of their support. The best organisations try to meet this need, while understanding the challenges involved. They're humble, shifting the emphasis away from their own work and onto the stories of the people involved and lives changed. They're curious, taking extra steps to articulate the real human impact of their work, rather than using abstract concepts like 'reducing isolation'. They're respectful, working with frontline staff and service users to measure impact in more natural, less intrusive ways and focus on empowering messaging and positive imagery. 💷 Invest in fundraising - even if you have the very best fundraiser and most compelling cause, you can’t magic up results unless you’re willing and able to put in place the required capacity, expertise and supporting resources. All your fundraising activity should start with an honest conversation about what it will take to produce and sustain results. Keep your expectations in proportion to your investment - if you can't invest properly in everything, narrow your focus to fewer activities that you can do well, and avoid spreading yourself too thin. 🧠 Trust the experts - good fundraisers have been doing things for a long time and have an instinctive feel for what a realistic return looks like and what they need to succeed. It can be dispiriting and counter-productive to undermine that experience because someone is trying to push through an idea that they personally think is brilliant, or has worked in a completely different context, but which isn't a good fit for your own carefully-crafted strategy. So when your fundraiser tells you that writing to Bill Gates or planning a golf day aren’t a good use of their time, please try to listen! ⚠️ Balance risk and innovation - that said, some ideas are worth trying, even if they’re not guaranteed to succeed. Fundraising innovation and growth are vital, but can be all too easily be stifled when people are excessively risk-averse. By all means question a new fundraising idea and do your due diligence. But remember that often the biggest risk isn't trying something new, but doing nothing new for 10 years and watching your 'safe' income streams dry up until it's too late to replace them. We've written more on balancing risk and reward here. ❤️ Value donors - donors are people, not cash cows, but it’s too easy to inadvertently treat them as the latter when you’re short on time and money. This is a fundraising topic as old as time, and we don’t have much to add, but the best fundraising charities take time to say thank you brilliantly, prioritise building relationships and learn what makes their donors tick. It’s the right thing to do, it benefits the whole sector, and the money will almost always follow. But wait, there's a caveat… ⚖️ Embed an ethical approach - sources of funding are complicated, donor behaviour is often far from perfect, and there are huge power imbalances in our sector. So let’s be clear: valuing your donors doesn't mean putting them on a pedestal, condoning everything they do, and shying away from challenging them when needed. While the obvious answer is to create an ethical fundraising policy, this is only part of the puzzle, and never works well as a tick-box exercise. If you want to tread a truly ethical path through a minefield of nuanced issues, you need to empower your team to debate some tricky decisions and feel comfortable to raise concerns when needed. What have we missed? What would you add to this list, based on what your organisation does well or what you've seen someone else do brilliantly? Let us know in the comments below ⬇️ INVOLVING FRONTLINE STAFF IN PLANNING YOUR FUNDRAISING STRATEGY - WHY BOTHER, AND HOW CAN YOU DO IT?9/10/2023 One of our main areas of work involves helping organisations to develop a new long-term fundraising strategy. Often the same question comes up early on when planning the process: who should we involve? For reasons that we've shared before, our process is very much not to sit in a room alone and write a fundraising strategy using a template. Instead we take a collaborative approach, facilitating a series of workshops to involve as many people as possible in the challenge of making fundraising more sustainable and successful. This involves mapping out key barriers and opportunities, developing clear strategic priorities, and identifying how the whole organisation can pull together better support good fundraising. So far, so good. But who should be involved in that process? Traditionally it’s the fundraiser(s) themselves, the senior management team, and representatives from the Board. All these people do indeed have a crucial role to play in making then enacting the key decisions. But if you stop there, you’re risking limiting your perspective, therefore creating a weaker fundraising strategy. The aim of this blog is to convince you that involving your frontline staff in developing your fundraising strategy is important. So what are the benefits?1. Frontline staff are closest to your service users, so can better articulate their views and needsDepending on the nature of your work, the people that you support – and their families – can be a real engine when it comes to raising money, advocating for your work, and opening crucial doors for fundraising. But how might they want to be involved? What are their concerns and barriers? And what do they need from you to feel equipped to play a role? Answering these questions will help you to plan fundraising activities and decide how to resource them. While it probably won't be practical to involve these people directly in your strategy process, your frontline staff do have a good relationship with them, so will know how best to gather, represent and respond to their needs and wishes. They'll certainly be better placed to this than your management, or even your fundraiser(s). 2. Frontline staff bring crucial insights about your workDeveloping a fundraising strategy in isolation of your service delivery means you’ll miss out on crucial "crossover" observations. For example, how well your services are performing – and how you’re collecting impact data – directly impacts your ability to secure grants. The activities that you run, and the spaces where you run them, can provide an untapped opportunity to raise money, recruit supporters and develop new earned income opportunities. It's easy for management and fundraising staff to make assumptions about what your key opportunities and barriers are. But if these assumptions are wrong, you’ll make the wrong decisions, and invest time and money in the wrong areas. Again, your frontline staff can provide essential insight. 3. If frontline staff are involved in planning your strategy, they’ll be better advocates and ambassadors for your fundraisingWe all struggle to get on board with a strategy that we haven’t contributed to or been asked about. It’s just an abstract document that, at best, we read then forget about. But when people are involved in the process and can understand your decision-making, and the need for better fundraising to safeguard the future of your organisation, they’ll be naturally more engaged in making it a reality. I’ve seen it so often - a CEO says that frontline staff won’t want to be involved in the fundraising strategy, won’t have anything to say, won’t have time to contribute. But when you involve them, they’re enthusiastic about being able to share their perspective, buy into what you’re trying to achieve, and become more motivated about their own role (even if it’s a small one) in making your fundraising more successful. But how can you realistically involve frontline staff in your fundraising strategy process, when they don't have any time to spare?1. During your first strategic planning sessionOur strategic planning workshops always follow a similar pattern: the first session(s) focuses on “discovery” – with everyone getting all their ideas, observations and concerns out in the open, then the later session(s) are dedicated to decision-making using that information. While your frontline delivery staff may very well not have the time or appetite to participate in the full process, asking a few representatives to come along to the first workshop – even just for the first couple of hours – may be a handy compromise approach, to ensure their views are factored into your thinking. 2. Requesting their views via their line managerWe’ve worked with organisations who have gained really helpful insights by asking their Service Manager(s) to coordinate gathering feedback and ideas from their own particular team. This can be done during regular team meetings, one-to-one conversations or a dedicated short workshop session. Managers can then collate feedback and share a summary with whoever is leading the fundraising strategy process. While this approach may only capture a few headline ideas, it’s a helpful light-touch option where frontline staff are stretched to capacity already. 3. Creating an online surveySimilarly, you can collect brief feedback by asking frontline staff to complete a five-minute survey. I’ve seen organisations gather surprisingly helpful insights by asking just a handful of carefully-worded questions, such as “What is the biggest thing that holds back our fundraising?” or “What do you think is our biggest missed opportunity with fundraising?” While it'll require a few reminders to ensure enough responses, it’s worth the effort. Even a single-page summary of collated ideas can be a valuable input into your fundraising strategy process. It’s easy to skip gathering input from frontline staff, assuming they lack either the time or knowledge to help. But finding ways to involve them in the initial stages of a fundraising strategy process will help you to gather invaluable ideas and perspectives, and ultimately develop a more successful and achievable fundraising strategy.

By the way, while we've focused on fundraising in this blog, many of the same principles apply for an organisational strategy too. We’ve facilitated fundraising strategy workshops and consultation processes for hundreds of charities and social enterprises. If you think we could help you, don’t hesitate to get in touch.

The cost-of-living and energy crisis is the latest major headache for charities and social enterprises, with many experts now predicting that the impact could be more severe than the pandemic.

When the outlook is so serious, and you have a million other things to do, it might be tempting to put off thinking strategically about this, and simply hope that the worst projections don't come true. But - I can’t stress this enough - this is a crisis to tackle head on, because there are things you can do to navigate your organisation through the worst of it. Firstly, how will charities and social enterprises be impacted?

As costs increase, the real value of existing grants and donations goes down. Again, let’s look at what Pro Bono Economics say: a grant worth £100,000 per year in 2021 will only be worth £94,000 by 2023, and a monthly direct debit of £20 in 2021 will have effectively depreciated to £17.20 by 2026. These figures are all based on inflation estimates that may already be too optimistic.

All this points towards you having to spend more to achieve the same impact - bad news, especially if you’re reliant on funders with antiquated views on how much things cost, and what they're willing to fund. But charities can’t control inflation and rising energy costs - so what can you do in response?1. Urgently re-budget

Before deciding what action to take, you need to understand exactly how your organisation will be impacted. This will depend entirely on your circumstances and what you do.

I believe that every Board and senior management team should be meeting as a matter of urgency and going through their budget with a fine tooth comb. Involving your fundraisers in this exercise will help them to understand key issues and make a stronger case for support later. For example:

Budgeting for these cost increases - both those that you have no control over, and those that you want to implement if funding allows - can be a stressful exercise. But it’s vital to look for these dangers ahead of time, as it'll put you in a better position to respond appropriately (see below). 2. Ask funders (and donors) for help

As with other recent crises, how well the voluntary sector can survive the storm depends on whether funders step up to the plate. I'm really hoping they will, especially if enough people ask the right questions.

If you’re currently in receipt of a multi-year grant, contact the funder and explore whether it's possible to renegotiate the grant amount for future years, based on the unexpected and unavoidable rise in your costs. If you’re considering applying for a new grant but the funder’s criteria are very restrictive - for example if they’ve had the same blanket rule for years about how much you can include for overheads - explain how your budgeting shows that this is no longer viable for your organisation, and ask whether they can offer any flexibility given the current crisis. By doing a proper re-budgeting exercise in advance, as described above, you can make a more convincing argument to funders, and portray your organisation as financially responsible. Many funders did show an admirable level of flexibility and understanding during the pandemic, and they genuinely want to help, so don't be afraid to ask these questions. To give an example that we've shared previously:

And like I always say, if a funder’s restrictions or policies put your organisation at financial risk - for example, if they won’t include a contribution towards running costs or allow you to budget for inflation - don’t be afraid to walk away if necessary.

Asking for help applies to other fundraising audiences too. If I were a Fundraising Manager at any organisation right now, I'd be developing some honest and carefully-worded messaging about the impact of rising costs on our work, to share at the appropriate time with regular givers, major donors and corporate partners. Of course not everyone will be in a position to increase their donation, but few will resent being asked. If any of the charities that I currently donate to contacted me to request a 10% increase in my monthly direct debit, to ensure they could sustain their impact amid rising costs, I’d be doing whatever I could to help. 3. Look for cost savings

This crisis isn’t your fault, but there will still be things you can do to make savings, even if this only makes a modest difference in the face of rising costs.

For example, here's some excellent advice from small charity finance expert Liz Pepler on how some charities can make savings by claiming reduced VAT on fuel and power, as well as maximising Gift Aid:

Spend some time identifying your own biggest potential saving areas and researching cost-cutting techniques - there are many excellent tips out there. For example, I’ve heard of organisations compiling energy-saving tips for staff, changing cooking techniques and recipes, and reviewing routes and providing fuel-saving tips if they do a lot of driving. Just watch out for scams or anybody trying to sell you something that sounds too good to be true.

Finally, some helpful links for further advice

According to Wiktionary, the above proverb is used to describe "a disappointing or mundane event occurring straight after an exciting, magnificent, or triumphal event." Now it's a stretch to call any strategy process magnificent or triumphal - I love strategic planning and even I wouldn’t go that far. But you can probably remember a time when you saw a new strategy launched with much fanfare, the product of many exciting conversations about the future, and then…nothing. The strategy goes to its final resting place in a dusty drawer or the dark recesses of your shared drive, and everybody goes back to their daily business as if nothing has changed. This is a huge waste of time. Everybody knows it, but it still happens more often than most people care to admit. At Lime Green, we try to make any strategy process as collaborative and inclusive as possible - I'm a firm believer that the conversations are as important as the final document. You need to involve people from all levels of your organisation, rather than entrusting a senior leader or consultant to sit in their ivory tower and write your strategy alone. But this alone isn't enough to avoid the pull of the strategy graveyard. There are loads of resources out there about how to create a strategy, but very little on the all-important topic of what to do after you've finished it. So here are some tips for making sure your published business plan or fundraising strategy remains a useful and relevant guiding document… Organise launch sessions for all staffExpecting everyone to independently read and engage with a new strategy is a tough ask. Even if they want to, the realities of their job may get in the way, and words on a page are rarely that exciting or inspiring. This is where a strategy launch session - for the whole organisation or your particular team - can work really well. Ask people to read the strategy in advance, but be prepared to summarise key points at the start. Encourage staff to ask questions, voice concerns, and think creatively about what they need to start doing differently to turn the strategy into reality. While this absolutely isn’t a substitute for involving people in the planning process, it's a great additional step. Providing a space to discuss concerns is important, because a new strategy can inadvertently make people worry about things like job security or underinvestment in their area of work. Dealing with these worries head-on will reassure people and make them engage more positively with what you want to achieve. Update your budget, plan and other resources to reflect your strategyIf a strategy is meaningful and well thought out, it should ultimately result in you changing the way you work - but it's not the strategy itself that does the heavy lifting. It’s highly likely you’ll need to update your budget and re-write your operational plan. Job descriptions and even job titles may need to be changed. Regular meeting agendas will need updating, so you can monitor and discuss the things that you’ve decided are most important. Forget to do this and your strategy quickly becomes irrelevant, because people won’t have the resources or permission to start doing things differently. Shout about your strategy to service users, partners and fundersA good strategy, with a bold vision and clear direction, should build confidence and trust in your organisation and improve how you work with others. If that’s the case, you want it out in the open. So make sure that everyone you work with knows about your strategy, understands how it changes things, and holds you to account for turning it into reality. But you can’t expect your strategy to be important enough to external people that they’ll sit down and read it in full. There may also be parts of it that are for internal eyes only. This is where a well-written executive summary or eye-catching infographic, which summarises key information in a concise and engaging way, can be hugely helpful. Make your strategy visibleI don’t just mean saving it somewhere easy to find, although that helps. If you've created a clear list of strategic priorities, milestones or values, make these impossible to miss. Print them and stick them up in your office and meeting room. Add them to login screens, backgrounds and screensavers. This makes your key messages impossible to forget and ignore, but it also shows pride in your strategy and promotes accountability - because someone, somewhere is going to look a bit silly if the whole team gets a daily reminder of all the things that the organisation changed its mind about doing. Show how your strategy is helping to achieve successIf colleagues are wrestling with a tricky decision, remind them to refer back to the strategy and consider how it could guide them. If following your new strategy has enabled some kind of success - securing a new grant, forming a new partnership or receiving positive feedback - shout about it from the rooftops. In my experience, there are enough badly-planned and painful strategy processes out there that a lot of people approach this type of work with a big dollop of suspicion and scepticism. Showing the value of a good strategy, and vindicating the time spent on it, can help to change attitudes. You'll be grateful the next time you need their time and input. Commit to a strategy reviewNo strategy gets everything right or accurately predicts the future. But that’s never a reason to hope everybody quietly forgets it ever existed.

To get real value out of a strategy, you'll need to review it part way through the strategic period, say after 12 or 18 months. Committing to this in the strategy itself, and scheduling a review process well in advance, makes it far more likely it'll actually happen. Just before you publish a strategy is a great time to identify anything that will particularly merit a review. If you've faced a particularly tough decision, or committed to a direction that some staff are worried about, then promise to revisit this. Thinking like this may give you a list of natural questions to work through later. This again builds confidence and accountability, and might persuade doubters to give something a try for a bit. This month we're taking a breather from writing punchy opinion pieces or gazing into our crystal ball and focusing on something more straightforward but still vital - everything you need to know about the humble case for support. What do we mean by a case for support?A case for support is an internal document that you create to outline the problem your organisation exists to solve, what you do about that problem, and what you're going to achieve as a result. Quite literally, it's your case for why donors or funders should support your work. A good case for support effectively acts as a comprehensive, well-organised filing cabinet of convincing content that you can pull out whenever you need it - for a funding proposal, a meeting with a donor, to create copy for a webpage. It’s very unlikely that anyone outside your organisation will see - or would ever want to see - this full document in all its glory. But it should be the starting point for your external, donor-facing documents. It's never a case of just copy/pasting large chunks of content from your case for support into an external document and just adding images and a catchy title - the text will always need tailoring for the audience and context - but it’s still a brilliant shortcut. (Just to confuse things, often organisations create a shorter, branded external document to 'sell' their work to donors and also call this a ‘case for support’, but that’s not what we’re talking about in this blog.) Working with organisations to create their case for support is one of my favourite jobs. As well as it being a privilege to learn all about fascinating and important new causes, I love the process of asking a few targeted questions, rapidly building up an array of content on colourful post-its, then shaping it into a structured document. And organisations always seem to really value having that outsider’s perspective - while they can supply all the passion, lived experience and raw content, a few ‘devil’s advocate’ questions from us can help to clarify details, tease out vital extra information and explain things clearly and convincingly for an external audience. What are the benefits of developing a case for support?Many organisations shy away from creating a case for support, because they don't feel they have time. I’m not going to lie, it does take time to create. But it will certainly save you time in the long run, and also increase your return on investment from fundraising. A good case for support will equip you with:

What should you cover in your case for support?There are many ways to structure a case for support, and they can get pretty long and complicated, but fundamentally you need to cover four key areas: The need for your work:

Your ‘solution’:

Your impact:

Your expertise and credibility:

Where can you go for the information needed to create a strong case for support?There are loads of potential information sources to draw on, but here are a few:

This can feel like a daunting process if you’ve never done it before, but it's important to stress that you don’t need everything to get started. As it's an internal document, developing a case for support can be an ongoing, iterative process - start ASAP, but make a note of what else you'll need to research, gather and add over time. The best cases for support are never finished, they evolve over time. For example if new research is published that reinforces the need for your work, or if you've just written a brilliant answer (even if you say so yourself) to a specific funder question that you want to re-use in future, find a place for it in your case for support. If you're now convinced that you need a case for support, what should you do next?We’ve tried to write this blog as a stand-alone free resource for anyone wanting to get started on their case for support. Remember that you're the expert on your work and the reasons why you do it, and your case for support is just a way of laying all that out in a logical, structure way.

If you feel you do need some extra support, we’ve got a couple of options:

There’s rarely a convenient time to be able to take a step back and commit to working on a new strategy, but recently it's felt harder than ever. We’re nearly two years into a pandemic that has kept everyone guessing and in firefighting mode - and with a new variant raising the stakes again, sadly there’s no let-up in sight. But with so many things having changed since the start of 2020, if you haven’t done a strategic refresh yet, now might be the time to take the plunge. Creating a new strategy is a unique process for every organisation - you’ll be facing your own cocktail of opportunities, barriers, community needs and tricky decisions. However inconvenient, there’s no definitive list of topics and issues that everyone should work through. That said, we're seeing a number of themes that keep coming up in our conversations with charities and social enterprises. So here are some key topics to have on your radar - you'll be able to decide how much each one applies to you… 1. Staff burnoutYour team may now have spent nearly two years battling through rising community need, pressure to stay financially afloat, and uncertainty around where and how they do their jobs, combined with personal concerns about health, job security and the impact of multiple lockdowns on mental health. Few people are feeling energetic or clear-headed, and the festive break (if we get a proper one) won’t be a complete reset. Any strategy that doesn’t acknowledge or address this risks falling flat, no matter how good the rest of your decisions. Talk to your team about how they're genuinely feeling, and what they need to have in place to do their jobs to the best of their ability in 2022 - which could mean more support, flexibility or encouragement than they previously needed. That might have an unexpected budget implication, but leaving people to just muddle on through could cost you more in the long run. 2. Hybrid delivery and digital exclusionShould we go back to running meetings and services in person, or keep them online? This was already a dilemma, even before the Omicron curveball. During the initial lockdowns, many organisations realised they could reach new people and deliver services more cheaply online. On paper, this seemed like a surprising positive from the pandemic, but there’s been rising concern about digital exclusion - who are we inadvertently leaving behind, and does digital delivery exacerbate inequalities? And there’s the added complication of how - and whether - to cater for everyone when some people want to be in a room with you and others want to participate remotely. These are key strategic challenges to wrestle with. Check out our original blog on digital exclusion from early 2021, our guide to running engaging and accessible strategy workshops online, and Zoe Amar’s excellent tips on making the right decisions about hybrid working. 3. Building long-term relationships with fundersFor me, one highlight of the past two years has been seeing funders engage more meaningfully and collaboratively with charities. This started with the collective commitment to flexible funding and reporting early in the pandemic, but has continued as many funders have acknowledged that grassroots community organisations are best placed to be their eyes and ears on the ground in a rapidly-changing landscape. But too many organisations are missing opportunities to build meaningful, mutually beneficial relationships with funders. Amid the pressure to bring in new grants and submit more applications, it’s too easy to neglect the positive impact of things like a well-written and honestly reflective grant report to an existing funder. And if we only value conversations with funders that are about immediate financial impact rather than learning and collaboration, we risk prioritising short-term target-hitting over long-term growth. While I get that organisations living hand-to-mouth will struggle to prioritise long-term relationship-building, if you have the breathing space to build this into your strategy, you'll soon see the benefits. Our recent blog on building relationships with invitation-only funders is a starter for ten here - we’ve had feedback from several funders that these are exactly the things they’re looking for. 4. Capitalising on that surge in public fundraising, donations and volunteeringWhile this felt particularly pressing back in spring/summer 2020, it’s not too late to bear in mind. The amazing community response to Covid-19 saw many people get a new taste for donating, fundraising or volunteering. Crucially, many actions were all about grassroots humanity - helping your neighbour with their shopping, or donating to the local foodbank. While big charities have household name brands, finely-tuned structures and economies of scale, grassroots organisations could promise immediate impact and a direct connection to those in need. Some charities have done an exceptional job of nurturing this - continuing to inspire, engage and connect new donors and volunteers through stories, events and further opportunities to make a difference. Treated right, these people have the potential to be their loyal regular givers, major donors and community fundraisers of the future. Have you benefitted from a surge of grassroots support during the pandemic? What have you done to keep that passion and humanity burning? And what can you still do to nurture and replicate it in future? 5. The way that people come together (or don't) is changingBeyond the physical lockdowns, the pandemic is having a long-term impact on how people behave, consume, congregate and interact. Offices have remained half-empty and high streets still feel eerily quiet. I was in central Bristol last Friday to buy my daughter’s first pair of shoes and most shops were deserted, two weeks before Christmas. This has massive implications, particularly for fundraising. ‘Old ways’ of doing things no longer feel fit for purpose, maybe permanently. What does it mean for corporate fundraising if most employees are never in an office together? How will your previous major donor tactics work if you rarely get to ‘work the room’? When we finally catch a longer break between variants, maybe some aspects of our pre-2020 life will gradually return. In the meantime, activity plans and budgets need to look very different. If you’re still spending more time designing printed materials than landing pages, or more money on branded stationery than search engine optimisation and social media advertising, you need to have a very good reason. Few of us can afford to wait until we can get people in a room together again before resuming our public fundraising. 6. The source of your donations is more important than everNearly 18 months on from the toppling of the statue of Edward Colston - just two miles from my house - philanthropy and ethical fundraising remain hot topics. In the past few weeks, we’ve received more enquiries about ethical fundraising reviews than pretty much anything else.

Many organisations have woken up to the importance of understanding the source of their donations and grants. What created that wealth in the first place? Are people and companies using philanthropy to ‘buy a seat at the table’ and gain influence over things like equality, social mobility and climate change? If your organisation is complicit in that, is this an unfortunate necessity in a tough financial climate, or an unforgivable oversight? These are difficult questions with no easy or short-term answers, but if you’re working on a new strategy then it might be time to put them on the table. We’ve shared a few ideas and potential solutions in various talks and blogs recently – this slightly provocative piece is probably the best starting point. Amid the many challenges we’re facing as a sector, one difficulty that predates the pandemic is recruiting the right fundraiser. Put simply, there are a lot of organisations out there looking for talented fundraisers, and not enough of them to go around. We've worked with countless small to medium charities who have had to go through multiple recruitment rounds, each time tweaking the job description and bumping up the salary in the hope that it'll make the difference. While they may get there in the end, they often don’t find the perfect candidate and/or they end up overpaying, and there’s certainly an opportunity cost associated with the months lost to a drawn-out process. There’s been plenty of reflection around this fundraising recruitment crisis, with fingers pointed at vague job descriptions, unimaginative person specifications and unrealistic expectations - and the broader, existential issue of whether enough people value and understand the charity sector and fundraising profession. I’m not a recruiter, but I’ve been around enough charities in this position to understand many of the common problems, and know a few things you can do if you’re struggling to find the right fundraiser: Who's actually auditioning? It's time to rewire your brain...A common assumption with fundraising recruitment, especially if you're new to it, is that you're the one running the audition. You might expect to welcome a conga line of candidates through your door, and give each one a thorough grilling to decide if they’re right for you. But in a market of few great fundraisers, it's very much a two-way process. Talented candidates know they have plenty of opportunities to choose from, and won’t necessarily rush to jump into a new role. They’ll want to put you under the microscope too, to understand the requirements and expectations of the job, and evaluate whether you can offer them the right environment to succeed. Rewiring your brain to this reality will help you recruit more successfully. In your advert, candidate pack and interview process, you need to give a flavour of your organisation’s approach to fundraising. For example, how does your organisation work with and support a fundraiser to make sure they have all the information and tools they need? Is your Board engaged in fundraising, and what does their involvement look like? How have you arrived at any targets you've mentioned? Allow plenty of scope for the fundraiser to ask you detailed questions. It’s absolutely their right to challenge you too, and it’s a positive sign if they are clear and even a bit demanding about what they need and expect in order to succeed. Create your fundraising strategy before you go to marketOrganisations looking to make their first significant investment in fundraising naturally target the perfect all-rounder - someone who can both create and execute a knock-out fundraising strategy. But there are numerous problems with this approach. Firstly, you’re looking for very different skillsets – there are experts in strategic planning and analysis, and experts at doing hands-on fundraising, but far fewer that excel at both. By trying to cover all bases, you risk narrowing the field and compromising in a key area. Secondly, if you haven’t analysed your organisation’s current position and best income opportunities, how do you know what type of person you’re looking for? Do you need an events expert with a bit of individual giving experience? Or is it more important to find someone who feels comfortable asking for major gifts face-to-face from wealthy individuals and in corporate pitches? Without a strategy, you often end up writing a vague job description and unrealistic person specification that require a bit of everything. Even worse, there may be a vague fundraising target attached to it that you've never tested, to determine whether it's realistic. You might think that “this sort of challenge will appeal to the right candidate” but in my experience it’s very off-putting. Successful fundraisers will smell the lack of clarity a mile off. Why would they pack in their current job and take a punt on a new role where, two months in, they might realise they’re not actually the right person for that organisation, or that the job isn't right for them? If you’re struggling to recruit a fundraiser, or have a limited budget to play with, creating your fundraising strategy first is potentially the most cost-effective approach. Invest a bit of money now in strategic consultancy support or an interim Fundraising Lead, get all your ducks in a row, then recruit the permanent fundraiser. By taking time to clarify your requirements, you’ll not only increase your chances of finding the right person, you might avoid having to throw so much money at a candidate too. Use your imagination and widen the fieldMost person specifications narrow the field far more than you realise, particularly after a pandemic that’s led many of us to reimagine how and where we want to work.

Before recruiting, ask yourself some questions. Do we really need to insist on (or even say that we prefer) candidates having a university degree? Is five years’ experience in a particular fundraising area really necessary? Are there transferrable skills from other sectors that we could look for instead? And while you're there, think twice about whether you really need somebody to be office-based and work five days per week. #nongraduateswelcome have done phenomenal work to highlight recruitment requirements that are not only unhelpful but, worse, discriminatory and against the values that the organisation supposedly stands for. Often, charities are seemingly on autopilot, including these requirements simply because everyone else is. Building your person specification from the bottom up – based on what you actually need, rather than what you think ought to be there – is not only the right thing to do, but makes it more likely you’ll find the right fundraiser for you. We work with many charities and social enterprises who are trying to get new fundraising income streams up and running and/or are tight on unrestricted funds. Perhaps it’s not a surprise that we sometimes get asked if we’d consider working on a commission or performance-related pay basis. I can see why, at first glance, this might appeal to organisations that have limited cash available to resource fundraising, or feel nervous about committing to expenditure without a guaranteed return. Investing in fundraising often feels like a Catch-22 situation, particularly when you’re prompted to do it because other funding sources have dried up. However, there are many reasons why payment by commission is actually harmful to you. The simplest answer is that the Institute of Fundraising discourages both fundraisers and charities from taking this approach, however this in itself doesn’t explain the challenges and issues that can arise as a result. Here’s why we don’t undertake any fundraising work on a commission basis, and why you should think twice about doing so: IT'S LIKELY TO PUT OFF FUNDERS AND DONORSIn fundraising you inevitably hear ‘no’ more often than ‘yes’, so a fundraiser working on a results basis would have to set a fairly high commission percentage to make it work. Imagine how a funder or donor would feel knowing that the first x% of their donation is going straight into somebody else’s pocket – particularly if they’re donating a large amount, and particularly at a time when there’s so much focus on how donations are used and what percentage is spent on overheads etc. Payment by commission can lead to you excessively rewarding a fundraiser, and is very likely to cost you donations. IT CAN PUT HARMFUL PRESSURE ON DONORS AND FUNDRAISERSFundraising is already a delicate balancing act between the financial needs of the organisation, the wishes of the donor and any ethical considerations. Now factor in a fundraiser who feels desperate to secure that donation, otherwise they won’t get paid. Sometimes we all have to walk away from potential donations, for example if the donor seems vulnerable and unsure about giving, or if the organisation may be compromised in some way by accepting. Paying a fundraiser on a commission basis makes it less likely they’ll make that difficult decision to say no when you need them to. IT GIVES THE WRONG IMPRESSION THAT FUNDRAISERS ARE SOLELY RESPONSIBLE FOR SUCCESSFundraising is a collective effort. When we work with an organisation, we may be responsible for crafting the ask and coordinating the process, but we can’t do it without you: your project information, your impact data and your contacts. If the fundraiser is the only one who loses out if things go wrong, you’re not creating the right conditions for success. When you pay a fundraiser a salary or a day rate, you’re making an investment in fundraising too, so the whole organisation has a vested interest in playing their part. IT UNDERVALUES SO MUCH IMPORTANT WORK THAT ENABLES GOOD FUNDRAISINGAs per Simon Scriver’s blog, a surprisingly small percentage of a fundraiser’s role involves asking for money. They spend most of their time researching prospects, building relationships, saying thank you, gathering project and impact data, and developing processes: this is essential for successful fundraising, even if it doesn’t always lead to a donation. If a fundraiser only receives commission, they’re not being paid for the vast majority of their hard work. So will they still feel motivated to do those all-important support tasks? If they're pressured into a quick-fire ‘spray and pray’ approach, this has a negative impact on your organisation. IT’S VIRTUALLY IMPOSSIBLE TO ADMINISTER IN PRACTICEFundraising is a long game. You might wait 6-12 months to hear back from a trust. A corporate donation or major gift is often years in the making. Several fundraisers may feed into the process (one makes the introduction, one writes the copy, someone else attends the final meeting). So how do you decide who receives what commission, and when? How do you avoid multiple fundraisers ‘competing’ for the same commission? How do you reward a fundraiser who moved on ages ago? And how can a fundraiser plan their income with so much uncertainty? IT ACTUALLY WORKS AGAINST SMALLER ORGANISATIONSWe work with a broad range of organisations, from start-up social enterprises with a £50,000 turnover to charities running multi-million pound capital appeals. The work involved with a £10,000 application and a £1million ask may actually be similar, yet payment on a commission basis values them completely differently. If a fundraiser is working on both simultaneously, with competing tight deadlines, you can imagine which one will get most of their attention, even if this is sub-conscious. So here's the clincher: payment by commission, which at first glance may seem so appealing to you as a smaller organisation, can in reality penalise you and de-value your donations. If you’re looking for fundraising support, get in touch with us now and we’ll explain exactly how our day rates and fixed fees work – but don’t expect us to use the word ‘commission’ at any point!

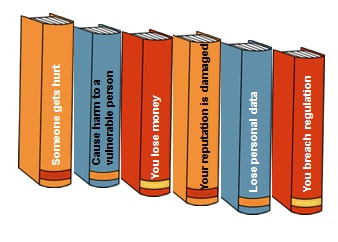

As an organisation, how do you manage risk in your fundraising activities? Do you focus on financial or reputational risk, or both, or other things too? Do you keep going until you’ve eliminated every possible risk from your plans? If so, are your activities still worth doing by the end? I recently popped along to the Arnolfini for the latest Bristol Fundraising Group talk about risk management in fundraising. The speaker was the excellent Ed Wyatt, an experienced Compliance Manager for multiple big charities and long-time fundraiser and trustee. Ed has kindly given us permission to share some key learning points here… The problem Conversations about risk in fundraising can be frustrating and unproductive. It can feel like natural risk-takers and risk-averse people are speaking entirely alien languages, and often the loudest voice in the room wins. This can have several consequences:

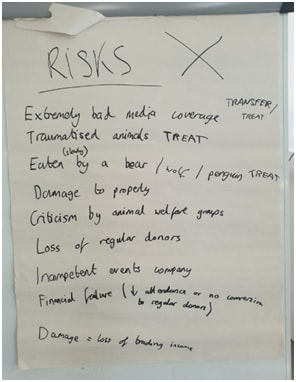

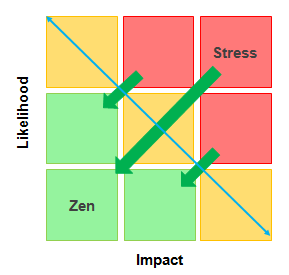

Reviewing your current fundraising portfolio, and where you might find The Next Big Thing In his talk, Ed demonstrated a simple way of reviewing your current fundraising portfolio and defining your activities using four categories: Low risk, high reward activities are the obvious sweet spot to aim for. Most of your fundraising probably falls into this category already but, since everybody else is thinking the same thing, the growth potential or uniqueness of these activities may be limited. Low risk, low reward activities might've been very easy to get approval for, but they may not be worth the effort. And in the unlikely event that you have any high risk, low reward activities, you should flag these up urgently. In both cases, terminating these activities could be a good way to free up capacity for something else. That leaves high risk, high reward activities. Scary territory, but if you’re looking for The Next Big Thing in fundraising, you may need to creep beyond your comfort zone into this space. To do this, first you need to define your organisation’s risk appetite (the blue line above) - the line you're willing to creep up to, but not cross. ‘High risk’ and ‘low risk’ are likely to mean very different things if you work for an international conservation charity with a history of provocative campaigning activities, compared to a local community library. Your risk appetite should depend on the nature of your mission, your beneficiaries, your financial position and the characteristics of your existing fundraising activities. It’s crucial to avoid being guided by anybody’s personal judgement, even management and trustees – we recently explored this same topic in our blog about ethical fundraising policies. It’s vital to remember that ‘high risk’ must never mean breaking the law, fundraising regulations, your internal guidelines, your ethical fundraising policy or your gift acceptance policy. Identifying risks in new fundraising opportunities Before you decide what level of risk you’re prepared to live with, you need to identify all possible risks associated with your activity or event. Ed suggested using your own ‘risk library’ of common categories that most risks fall into, for example: This works best as an energetic debate, not a dreaded tick-box exercise for one person alone behind a desk. Try to ask a few different personality types to sit in a room together and discuss - both natural risk-takers and risk-averse people have a key role here. You need to create the right atmosphere and reassure people that there are no right or wrong answers at this stage. This was illustrated nicely by a group exercise at the end of the talk. Ed asked us all to imagine we were the Fundraising Team at a local animal park, who had been approached by an events company with a new idea: a series of late-night parties at the animal park for 18-30 year olds. This would be a new and potentially lucrative audience for the charity, but hardly risk-free. My group had five minutes to consider all possible risks, and came up with the following: As you can probably guess, this was a light-hearted attempt at risk assessment. But Ed said that humour is a useful tool in real-life scenarios too. ‘Eaten by a bear’ might have been a joke, but it helps to highlight a real risk (injury inflicted by the resident animals) that the organisers of this event might otherwise have forgotten to flag up. Discuss how to manage risks but decide what level of risk you’re ultimately comfortable with When deciding what to do about each risk, use the Four Ts:

It’s crucial to adopt a varied approach. Tolerating everything would be reckless, but treating everything is likely to be exhausting and impractical. Transferring everything would be prohibitively expensive, and terminating everything would leave you with a vanilla fundraising activity, or no activity at all. By taking ownership of your risks, and making sure they’re all within an acceptable level, you can move to a more Zen-like state with your fundraising. Most lucrative fundraising activities carry some level of risk, so you need to think back to your risk appetite (the blue line below) and decide what level of risk your organisation is prepared to accept given the circumstances: Contrary to popular belief, compliance and risk management shouldn’t be about saying ‘no’ - it's more a case of ‘not like that’. Risk-free activities are rarely financially or commercially realistic, but that’s not an excuse for failing to take responsibility of the situation or control of your risks. In other words, don’t let your participants get eaten by a bear, but don’t let compliance bears eat up all your good fundraising ideas either. Huge thanks to Ed Wyatt for giving us permission to share his learning, including his diagrams, and introduce bears into the story for no particular reason.

|

Like this blog? If so then please...

Categories

All

Archive

May 2024

|

Lime Green Consulting is the trading name of Lime Green Consulting & Training Ltd (registered company number 12056332)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed