|

As an organisation, how do you manage risk in your fundraising activities? Do you focus on financial or reputational risk, or both, or other things too? Do you keep going until you’ve eliminated every possible risk from your plans? If so, are your activities still worth doing by the end? I recently popped along to the Arnolfini for the latest Bristol Fundraising Group talk about risk management in fundraising. The speaker was the excellent Ed Wyatt, an experienced Compliance Manager for multiple big charities and long-time fundraiser and trustee. Ed has kindly given us permission to share some key learning points here… The problem Conversations about risk in fundraising can be frustrating and unproductive. It can feel like natural risk-takers and risk-averse people are speaking entirely alien languages, and often the loudest voice in the room wins. This can have several consequences:

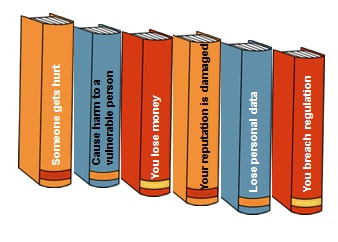

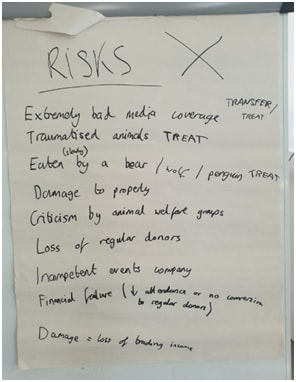

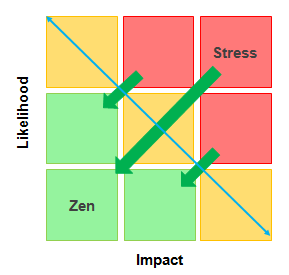

Reviewing your current fundraising portfolio, and where you might find The Next Big Thing In his talk, Ed demonstrated a simple way of reviewing your current fundraising portfolio and defining your activities using four categories: Low risk, high reward activities are the obvious sweet spot to aim for. Most of your fundraising probably falls into this category already but, since everybody else is thinking the same thing, the growth potential or uniqueness of these activities may be limited. Low risk, low reward activities might've been very easy to get approval for, but they may not be worth the effort. And in the unlikely event that you have any high risk, low reward activities, you should flag these up urgently. In both cases, terminating these activities could be a good way to free up capacity for something else. That leaves high risk, high reward activities. Scary territory, but if you’re looking for The Next Big Thing in fundraising, you may need to creep beyond your comfort zone into this space. To do this, first you need to define your organisation’s risk appetite (the blue line above) - the line you're willing to creep up to, but not cross. ‘High risk’ and ‘low risk’ are likely to mean very different things if you work for an international conservation charity with a history of provocative campaigning activities, compared to a local community library. Your risk appetite should depend on the nature of your mission, your beneficiaries, your financial position and the characteristics of your existing fundraising activities. It’s crucial to avoid being guided by anybody’s personal judgement, even management and trustees – we recently explored this same topic in our blog about ethical fundraising policies. It’s vital to remember that ‘high risk’ must never mean breaking the law, fundraising regulations, your internal guidelines, your ethical fundraising policy or your gift acceptance policy. Identifying risks in new fundraising opportunities Before you decide what level of risk you’re prepared to live with, you need to identify all possible risks associated with your activity or event. Ed suggested using your own ‘risk library’ of common categories that most risks fall into, for example: This works best as an energetic debate, not a dreaded tick-box exercise for one person alone behind a desk. Try to ask a few different personality types to sit in a room together and discuss - both natural risk-takers and risk-averse people have a key role here. You need to create the right atmosphere and reassure people that there are no right or wrong answers at this stage. This was illustrated nicely by a group exercise at the end of the talk. Ed asked us all to imagine we were the Fundraising Team at a local animal park, who had been approached by an events company with a new idea: a series of late-night parties at the animal park for 18-30 year olds. This would be a new and potentially lucrative audience for the charity, but hardly risk-free. My group had five minutes to consider all possible risks, and came up with the following: As you can probably guess, this was a light-hearted attempt at risk assessment. But Ed said that humour is a useful tool in real-life scenarios too. ‘Eaten by a bear’ might have been a joke, but it helps to highlight a real risk (injury inflicted by the resident animals) that the organisers of this event might otherwise have forgotten to flag up. Discuss how to manage risks but decide what level of risk you’re ultimately comfortable with When deciding what to do about each risk, use the Four Ts:

It’s crucial to adopt a varied approach. Tolerating everything would be reckless, but treating everything is likely to be exhausting and impractical. Transferring everything would be prohibitively expensive, and terminating everything would leave you with a vanilla fundraising activity, or no activity at all. By taking ownership of your risks, and making sure they’re all within an acceptable level, you can move to a more Zen-like state with your fundraising. Most lucrative fundraising activities carry some level of risk, so you need to think back to your risk appetite (the blue line below) and decide what level of risk your organisation is prepared to accept given the circumstances: Contrary to popular belief, compliance and risk management shouldn’t be about saying ‘no’ - it's more a case of ‘not like that’. Risk-free activities are rarely financially or commercially realistic, but that’s not an excuse for failing to take responsibility of the situation or control of your risks. In other words, don’t let your participants get eaten by a bear, but don’t let compliance bears eat up all your good fundraising ideas either. Huge thanks to Ed Wyatt for giving us permission to share his learning, including his diagrams, and introduce bears into the story for no particular reason.

1 Comment

|

Like this blog? If so then please...

Categories

All

Archive

May 2024

|

Lime Green Consulting is the trading name of Lime Green Consulting & Training Ltd (registered company number 12056332)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed