|

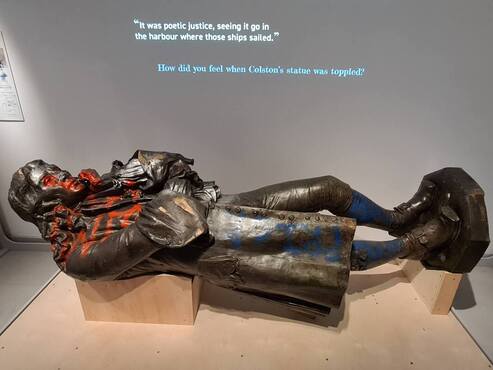

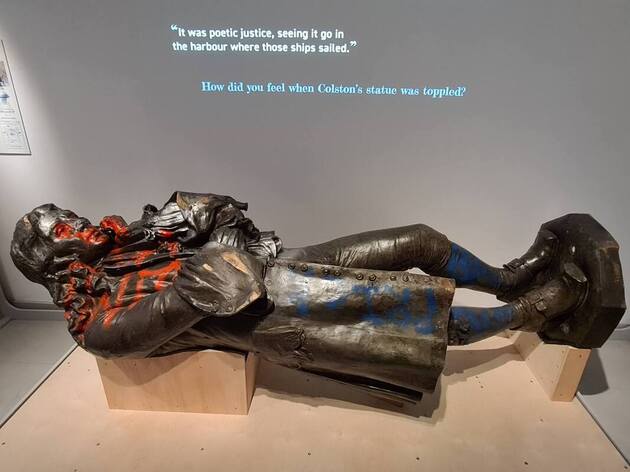

It’s been nearly five years since we first shared some tips on creating an ethical fundraising policy, and 2-3 years since we really embraced the complex debate about problematic philanthropy. To kick off 2023 on a thoughtful note, this new blog brings together those ideas - and some new ones - for anyone looking to create an ethical fundraising policy. Problematic philanthropy - not as clear-cut as it seemsSummer 2020: the statue of Edward Colston makes its journey from high-profile city-centre plinth to horizontal resting place in a Bristol museum, via a swim in the River Avon. The charity sector is awash with talk about the issues with accepting grants and donations linked to historical figures involved in the slave trade. There’s a clear view – philanthropy can’t be used to excuse or whitewash the injustice of how wealth was first made. Spring 2019: the Sackler Trust halts grantgiving in the wake of the Purdue Pharma scandal. The US pharmaceutical company, closely linked to the Trust, is accused of fuelling the US opioid crisis that killed almost half a million people, having spent years aggressively pursuing legal action so they could continue selling their highly addictive drugs. Slowly, UK cultural institutions like the British Museum and the National Portrait Gallery begin distancing themselves from the Sackler name. Clear-cut cases like this make us all understand the need to swerve “bad money”, and make the process of writing an ethical fundraising policy seem pretty straightforward. Except that (mixed metaphor alert) once you open this can of worms, you get hit by about a million grey areas. Consider the following examples: Despite the Colston backlash, there are plenty of other links between the slave trade and the charity / arts sector hiding in plain sight. Here in Bristol, the Society of Merchant Venturers continue to donate £250,000 per year to local causes. In London, the Tate Galleries continue to take their name from Henry Tate, whose Tate & Lyle sugar company was fundamentally connected to the slave trade. Many UK charities happily receive small-scale income via the Amazon Smile programme, despite Amazon being associated with a raft of harmful practices including “extreme tax avoidance, poor working conditions in factories, slave labour in their supply chain, and catastrophic environmental impact” (source: FRIDA). And how many charities have received grants from household name corporate foundations like the Lloyds Bank Foundation, Santander Foundation and the RBS Skills & Opportunities Fund? Yet consider this quote from a 2018 report by Ethical Consumer magazine: “The UK's big five high street banks [Barclays, HSBC, Lloyds, RBS and Santander] are hindering the sector's efforts to tackle climate change by continuing to profit from some of the world's dirtiest fossil fuel projects. [...] The UK's mainstream banking industry has involvement with virtually every ethical ‘problem sector’ from factory farming through to nuclear weapons.” The case against philanthropy - and the dilemma for charities and social enterprisesNone of this is about passing moral judgement on the specific names above, merely to demonstrate how much more complicated things are than Edward Colston and the Sackler Trust. An uncomfortably high number of philanthropists and foundations have clear links with the slave trade, climate damage, tax avoidance and damaging employment practices - all of which actively harm the very people many charities exist to help. As we argued in 2020, philanthropy buys a seat at the table for a very specific audience - wealthy, privileged, usually white and male. Through their decisions on what they do/don't fund, their roles on Boards and advisory groups, and their status as thought leaders, they gain disproportionate influence in implementing their own vision of equality, social change and climate justice - a vision that is probably very different from your own. This gives rise to some important questions about what criteria should you apply when evaluating donations:

Given this moral and philosophical minefield, how do you go about creating an ethical fundraising policy?Firstly, here’s how not to do it… Don’t go out and find a template ethical fundraising policy, copy and paste in some organisational details, and tick it off your to do list. As is usually the case, an honest, thoughtful discussion is a prerequisite to any good policy or strategy. Don’t base your decisions on the sum total of people’s personal beliefs, what you’ve seen other organisations do in the past, or what the loudest voices are saying (whether that's your senior leadership, trustees or existing donors). And don’t over-react to any specific recent event in the media. If you do, you’ll be basing your decisions on the wrong criteria, oversimplifying complex issues, and setting yourself up for trouble. You may later find yourself facing pressure to turn away a donation that technically contravenes your policy in an unexpected way, or facing criticism for accepting a donation that has implications you hadn't considered. The first step is to organise a structured discussion or workshop, involving people at all levels of the organisation. Start by explaining the context, giving some examples of problematic donations to consider, and outlining the risks of getting your policy wrong. Feel free to share this blog with everyone in advance. The vital context for any good ethical fundraising policy is YOUR specific work and mission. You should look to identify types of donor or donation that might:

As a general rule, if this discussion is quick and easy, and everyone is readily in agreement, you probably haven’t given it enough thought! You should aim to arrive at a list of criteria for donations that you’d definitely reject, and donations that would prompt additional action, for example further research into the source of someone’s wealth, an in-depth discussion with your trustees, or a consultation process with your service users. Once you’ve made some headline ethical decisions, you still need to decide how to implement your policyFor example, you’re likely to need a due diligence process for gifts over a certain value, guidelines for approaching vulnerable donors, and an ethical checklist for any new third parties or suppliers. To decide what specific processes and guidelines you need, you should carefully map out all the types of fundraising your organisation does, and the potential ethical risks with each. You also need to support fundraising staff who are at the frontline of putting your policy into action. They need a safe space to be able to raise and discuss any ethical concerns, and a complaints process if they feel the organisation is breaking its own policy. And they need a fundraising culture that isn’t simply about results at all costs. A good ethical fundraising policy is quickly compromised by demanding or unrealistic fundraising targets that encourage people to forget any concerns and just pursue the cash. Training and workshop facilitationHonestly, this blog could have been twice as long. There are countless other examples and considerations I could have included, but I hope this is a helpful starting point. While creating an ethical fundraising policy can be complicated, but it’s a really empowering and important thing to get right.

To explore things further, we run periodic talks and Q&A sessions on ethical fundraising and problematic philanthropy - check out our training page for more information. And we've also facilitated ethical fundraising workshops for organisations, focused on both challenging debate and concrete decisions. Get in touch if you'd like to explore how we could run one with you.

1 Comment

There's plenty to worry about at the moment - in fundraising and in society. With every passing crisis, charities and social enterprises face increasing need, but more financial pressure - and it’s no different now with rising inflation and the cost of living crisis.

On top of that, there’s much entrenched frustration directed at funders, whose grantmaking processes and policies add a further headache. Only last week, new research estimated that organisations spend £900million per year meeting the demands of applying to funders. Our own blog charts this rising frustration. We've written almost enough rants to fill a small book, whether about the human cost of bad application processes, the need for funders to turn over a new leaf, the injustice of the lack of infrastructure core funding, or the general frustrating things that funders say. While it feels important to be honest and realistic about these challenges, it's also nice to focus on positivity where we can find it. And it's true that the pandemic has prompted some positive reflection and reform from many progressive funders. When updating our training content recently, I really enjoyed preparing this slide highlighting some of the current movements and reports on grantmaking that give us reasons to be optimistic. I don’t think it’s a coincidence that it’s also one of our most colourful slides:

On the right of this slide is a book that I’ve been promising to review for months, because it gives a glimpse of a possible future for grantmaking that is better for everyone - more accessible, more respectful, more even-handed, and more impactful as a result.

Modern Grantmaking is written by Gemma Bull and Tom Steinberg. Both have worked for funders and been responsible for giving away money - a job that many people, particularly those outside the sector, might think sounds enjoyable and straightforward, but is actually fraught with challenges. Both have evidently experienced the creeping unease and frustration that comes with the territory of seeing money given away badly. So they sat down and spoke to countless experts about what the common issues are, and what good grantmaking should look like – and Modern Grantmaking is the result. Obviously, this book isn't written for people like me who seek funding, but for those on the other side of the fence who give money away and want to do it better. But for fundraisers, there's plenty of useful insight - and reassurance - in understanding more about the issues that grantmakers are wrestling with. The first reason for positivity is simply that a modern grantmaking movement exists. That a growing number of people in influential positions are talking and writing about how grantmaking isn’t good enough, and how it can be better. Early on, the authors write that in the last decade, such ideas are “growing up like green shoots through cracks in a pavement. These shoots are now so numerous and so vigorous that the paving slabs of traditional grantmaking practice are threatening to buckle.” Yet I wonder how many of these reformist ideas actually make it far beyond a tight circle of people. Certainly, the vast majority of fundraisers who come on our training courses and share frustrations about the things funders say and do, show little sense of this buckling pavement under their feet. So to have a new book that brings together these ideas, shouts about the need for reform, and signposts people towards a number of growing modern grantmaking movements, is a beacon of hope for fundraisers in a difficult landscape. As well as influencing funders, this helps to legitimise the frustrations that fundraisers feel, and galvanise them to find small ways to challenge and push back. If more of us are talking the same language, change happens faster. Last week, I saw a small but significant example of this on Twitter:

Modern Grantmaking gave me a telling glimpse into the curious career of a grantmaker - one with few structured development opportunities, and little incentive to do things differently. In the authors’ words, "grantmaking can also be an ideal career for people who just want a quiet life and a reliable salary.” Firstly, grantmaking comes across as at best a very young profession, and arguably not a recognised profession at all. The authors explain how there's no established career path into grantmaking, very little tailored training to help with the key skills required, and no accreditations or recognised standards to measure performance against. Secondly, there’s not much accountability. In a world without enough funding to go around, if a funder treats you badly, where are you supposed to take your ‘business’ instead? Can you afford to complain? If funders don’t recognise themselves as needing to provide a service to grantseekers, they won’t measure themselves in those terms. Reading this, suddenly many of my past experiences with funders made sense. Seeking funding is a lot like being a UK rail passenger - you might not enjoy the experience, it might feel unpleasant and at times dehumanising, but good luck finding an alternative. Now imagine the added fear that if you complain about the delays and overcrowding, they might simply stop offering you a seat at all.

It's cathartic to read this insight in Modern Grantmaking, and I'd recommend you do so yourself. But the best thing about the book is how it creates an alternative vision for grantmaking, as a profession with the service mentality, the standards and development opportunities, and the pressure to be better.

There's advice about how to recognise and manage the power and privilege that you have as a grantmaker. How to convince colleagues that you may not have the right perspective and lived experience in the room to evaluate funding proposals and make fair decisions. How easy it can be to strong-arm a charity into completely changing their project or budget, because of a seemingly innocuous suggestion you make. There are whole chapters dedicated to improving how you treat applicants, even if nobody is demanding it. How to understand what the experience is like for grantseekers trying to navigate your website, fill in your application form and go through the agonising wait for a decision - then take steps to improve that experience. A recurring theme is the importance for humility - just because you have all the money, it doesn’t mean you have all the knowledge. For grantmakers with this mindset, the book contains practical advice on how to commission independent research to understand a social issue well enough to judge funding proposals, and how to start reading evaluation reports with a critical eye that genuinely broadens your understanding, rather than just looking for quick evidence that your grants are working.

Reading all this was music to my ears as a fundraiser. And what makes Modern Grantmaking so convincing is that it’s peppered with horror stories of grantmaking done badly, and inspiring case studies showing how funders have reaped the benefits of making positive changes.

The book also has a real grassroots feel. While it may be picked up by the occasional Chief Executive of a funder, it's really written for those people whose day-to-day work has the power to make grantseeking a good or a miserable experience – the people who design application forms, respond to emails and answer the phones. Of course, we can hope that these people will still influence those working above them, and will ultimately go on to lead trusts and foundations in the future, and set a new standard for grantmaking. I hope that any grantmaker wanting to genuinely maximise their social impact will read Modern Grantmaking, then do what they can to push through change. I guess that will be the ultimate measure of the book’s success. But, in the meantime, if you’re a frustrated bid writer wondering if, how and when things will ever be done better, I’d also recommend getting yourself a copy - you’ll be able to take plenty of ideas and much-needed hope from it. You can buy your copy of Modern Grantmaking, and read more about the movement and the authors, by clicking here.

When the news that the Small Charities Coalition (SCC) is closing first broke, people expressed a range of emotions: shock, sadness, gratitude for their help, concern for the grassroots charities they support.

This is all justified, but I think there’s been too much resignation (that this is just one of those things that happens) and not nearly enough anger. I want to explain why this is a disaster - specifically for SCC and the many brilliant charities they support, but more broadly because of what it says about our sector and the lack of support for infrastructure organisations. This is a collective failure by grantmakers, resulting from short-sighted policy and too much ego.

First, a small disclaimer

I’ve been a pro bono trainer for SCC and general supporter of their work since 2015, so I can’t claim to be 100% neutral, although I should emphasise that we've never received any payment from our work with them.

Secondly, I don't have any knowledge of the inner workings of SCC, or exactly what they've done to try to secure funding. I'm sure there will have been things they could have done better or differently - that's the case for all of us - but I don't think that would fundamentally change what I want to say. Why is infrastructure support so vital for charities?

The vast majority of charities and social enterprises are tiny organisations run by people with lived experience of the issues they’re addressing. I've personally worked with so many brilliant founders who have been full of knowledge and passion, but who haven’t benefitted from professional training or the best education, don’t speak English as a first language, or have little money for professional development.

Inevitably there are times when they need expert support in areas outside their comfort zone - for example finance, fundraising or IT - but they don't have the budget to recruit a specialist staff member, or pay a consultant. Sometimes they secure ad hoc pro bono support from an expert – frequently a wealthy person in the twilight of their career after spending 40 years making money in the finance and business worlds, often perpetuating the same social issues they now claim to want to solve. For obvious reasons, this isn’t - and shouldn’t be - a solution for everyone. I’ve seen a few people argue recently that local infrastructure organisations can step up to the plate after SCC closes. Indeed I've come across some truly brilliant local services. Yes their support is excellent, and yes being localised is really valuable, helping to promote collaboration not competition between organisations. But in my experience, the quality of local support can really vary, and funding for it can suddenly evaporate in the winds of political change. It certainly isn’t available to everyone, everywhere. Economies of scale mean that most local infrastructure organisations can’t offer the same quality and cost-effectiveness as a national organisation. Even if they could, they'll still eventually face the same funding realities as SCC.

So national infrastructure organisations like SCC are vital - but who can we rely on to fund them?

Certainly not this government, which has alternated between being antagonistic and totally disengaged with the charity sector. As austerity has bitten, charities have necessarily become more vocal about the injustice faced by vulnerable people, and this government has worked progressively harder to discredit and demonise charities in response. Think back to how Conservative MPs seized on things like the Olive Cooke scandal.

Not the general public, who realistically will never be engaged with the nuances of how grassroots charities should be supported. Especially not when, following the lead of the government and the right-wing media, most public focus has been on red herrings like how many pence in every pound charities spend on ‘admin’, or how much their CEO is paid. This means we inevitably rely on grant funding - but funders haven’t stepped up to the plate

You could argue that it shouldn't be their responsibility, but then again, they’ve done it for countless other underfunded, niche and unpopular causes during a decade of austerity.

Funders are ideally placed to understand the value of grassroots charities, and the need to empower them. But astonishingly few have been willing to fund infrastructure organisations – and that’s due to short-sighted policies and too much ego in their decision-making. People with far more authority than me, including Paul Streets and Jake Hayman, have long criticised funders’ obsession with short-term, project-based impact, at the expense of strategic support, movement-building and core funding. This collective failure has gradually shamed grassroots charities into playing down their core costs and development needs, and systematically devalued learning, collaboration, professional development and long-term strategic planning. So many times, I’ve had to persuade small charity CEOs that they can include a contribution towards running costs in their project budget, and they do deserve to pay themselves a salary for their work. They’re terrified that they’ll be judged and penalised by funders. And sometimes, they're right. Contrary to what we’re often told, most grassroots charities don’t ‘waste’ money on salaries and running costs - they chronically underinvest in them. If, as a result, staff can’t or won’t pay for even low-cost training, infrastructure organisations like SCC can’t develop a sustainable business model – but they haven't been able to subsidise it through grant funding either. "Oh sorry, we really value the work that you do, we just can’t fund it ourselves." If a few funders say this, it’s their problem. But when almost every funder does, organisations like SCC fold, and that’s a problem for everyone.

SCC's closure is proof of this short-sighted grantmaking policy, but also problematic ego

Because well-funded infrastructure support does actually exist, just mainly in the form of Funder Plus programmes.

This sees funders often hand-pick a small number of their grantees to receive infrastructure support, mentoring or training alongside a grant. These charities aren’t the only people to benefit. Experienced consultants get to do exciting, generously-funded strategy and consultancy projects, either in-house for a funder or as a freelancer. I know, I’ve been one of them. I’ve previously been an advocate for the Funder Plus model because, in isolation, it achieves badly-needed, often transformational impact for a few charities. But if Funder Plus support comes at the expense of funding for centralised infrastructure support for everyone, it’s part of the problem - expensive to deliver, only benefitting a few, and driven by ego. "I want to decide which charities get support. I know best what types of support that people and organisations who are nothing like me really need. I want to see and shout about the tangible impact of my contribution, not fund an experienced, national organisation to do it at scale, for everyone." If this sounds like harsh criticism, consider this: SCC supports over 16,000 members and their annual budget has never topped £400,000, only rarely exceeding £200,000. They might have survived with just four or five moderate multi-year grants from progressive funders, or a smaller contribution from a slightly larger number of funders. That this has proved impossible is a damning indictment of our sector. How can you possibly argue that Funder Plus models achieve more impact and better value for money? I’m painfully aware that this comes too late to save SCC. That’s already a tragedy - but if we don’t use it as a wake-up call, we'll be facing an existential crisis. As a sector, we’re not so much shooting ourselves in the foot, we’re tearing out our own heart.

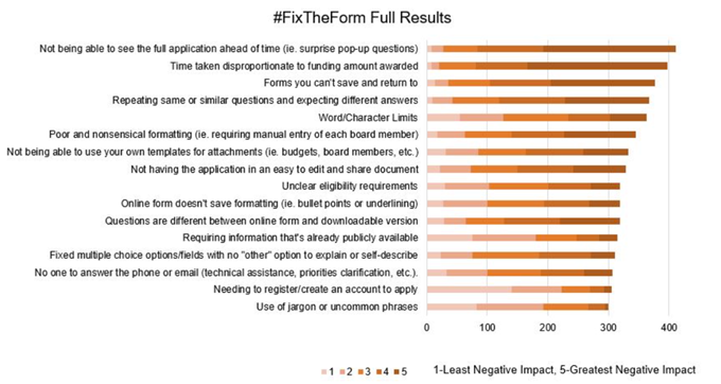

With great power comes great responsibility. (Who actually said that first? A quick journey down an internet rabbit hole suggests it could have originated from Voltaire, Spiderman, The Sword of Damocles or the French National Convention, which isn’t hugely helpful...) Either way, I think it’s a phrase that applies very well to trusts and foundations. When you give away grants, you of course aim to have positive social impact. However, you can also inadvertently cost good causes money, in the form of convoluted application forms, poorly-planned processes and unclear guidelines. These things waste the time of charity leaders, paid fundraisers and volunteers – and this has a huge opportunity cost at a time when we’re more overstretched than ever. Funders mustn’t be exempt from criticism for this, just because they give money away. Let’s not forget that philanthropists also get many benefits: tax breaks, public recognition (if they want it) and the ability to influence how we make the world a better place. I’ve previously written about why we need to change the way we view philanthropy, and the things that funders can do better to ensure they a net positive financial impact on the sector. But I want to forget about the financial cost of bad application processes for a moment, and focus on another aspect – the human cost. Here are a couple of examples from my recent work.  Back in the 4th Century BC, Damocles first shared his views on the responsibilities of funders and philanthropists. Possibly. Credit: Richard Westall - own photograph of painting, Ackland Museum, Chapel Hill, North Carolina, United States of America, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3437614 Example 1: The careless application deadlineRecently we were helping a client apply to the Postcode Local Trust. They open for applications on the first Monday of every month, but close as soon as they’ve received a certain ‘limited number of applications’ (a number they don’t actually publish). Will they stop accepting applications one week, one day or one hour after opening? Who knows, but imagine the frustration if you spend time working on an application that you’re then unable to submit. This is already questionable practice, but in May 2021 their application date coincided with the Early May Bank Holiday. We phoned them to check they were aware of this – they said that yes they were, and there was a good chance they’d close after reaching that maximum number of applications on that same day. One of our client’s staff team duly made a note to interrupt her day off – and day out with her family – to switch on her laptop, copy/paste the pre-prepared answers into the application form, and submit it before an unspecified number of other applicants (presumably sacrificing their own Bank Holidays) beat us to it. This might not be the biggest issue ever, but for me it’s the sheer pointlessness of it all. At a time when so many fundraisers are feeling under pressure and burnt out, why make things worse by coinciding your application deadline with a Bank Holiday? I can’t see how it brings any benefits for the funder – and a tiny change would’ve made a big difference for applicants. Becoming a Dad last year has given me a different perspective on these things. When you work long hours, your evenings, weekends and days off are a precious commodity. A carelessly-timed application deadline (or indeed, any form of unnecessary bureaucracy) no longer prevents me from doing things like having a lazy morning or going out for a drink – it stops me spending time with my family. Example 2: The unannounced grillingLast Autumn, I worked with a client to submit a ~£10,000 application to a local Bristol funder. After six months we still hadn’t heard anything, so assumed it had been unsuccessful. Then, out of the blue, the charity’s Director got a call from their administrator who launched into a series of on-the-spot questions about their accounts. As a small charity in a tight financial spot, this was a stressful experience – answering quickfire questions about an application they could barely remember, worrying that one slip-up might cost them a much-needed grant. Happily, the charity did eventually get the grant, but this still left a bitter taste in my mouth. Asking detailed financial questions is understandable, but why not put them in an email, or agree a time to speak in advance, to give applicants some time to dig out the application and the required detail? Most importantly, this risks skewing the application process. Answering detailed questions on the phone without warning will be harder for applicants whose first language isn’t English, smaller organisations with less financial expertise, and people who work part-time. There’s a risk that funding will be awarded based on which organisations answer on-the-spot questions better, rather than those who have the best projects or most social impact. Having accessible and reasonable application processes matters – so step forward #FixTheFormThese are just two examples of questionable funder practice, neither of which had much long-term negative impact. But magnify this across the whole sector – thousands of funders and millions of applications – and it’s a different picture. Badly designed application forms and inconsiderate processes waste time and money, create unnecessary barriers, cause anxiety, and divert people’s time away from much more important things – and frustratingly, it could easily be very different. One movement trying to change all this is #FixTheForm, an initiative of Grant Advisor. In November 2020, they surveyed 500 grantseekers in nine countries to catalogue their frustrations and pain points. This showed the same issues popping up time and again, with applicants losing hundreds of hours to badly designed forms and processes. According to respondents, the biggest issue was funders not showing their full application form at the start of the process: Perhaps these issues shouldn’t be surprising. While some funders might not be interested in making improvements to benefit applicants, many simply lack the time and resources. Maybe they don’t even understand the problems they’re causing – understandably, while many applicants would probably love to share feedback, they don’t feel that doing so while asking for money is a very wise idea. This is why #FixTheForm’s survey – and what they’re doing in response – is so important. Their new 100 Forms in 100 Days campaign aims to persuade 100 funders to join their growing list of ‘ReFormers’ by making a fully transparent application form publicly available on their website. With just over a month to go, they’re almost two-thirds of the way there. If you’re a charity or social enterprise, you can support #FixTheForm by sharing the 100 Forms campaign with your own funders, talking about it on Twitter, or looking out for future opportunities to share your application experiences with #FixTheForm. And Laura Solomons, who’s leading the #FixTheForm charge in the UK, is a great person to follow on Twitter if you ever want to discuss or draw attention to questionable funder practice. Neither of my recent experiences above would’ve been solved by a downloadable application form – but based on the #FixTheForm survey results, it’s a really important starting point.

Being a recipient of grant funding doesn’t mean you should simply be grateful and turn a blind eye to processes that make your life harder. Agitating for change is in everyone’s best interests – and if a funder is truly motivated to maximise their social impact, making these changes will be important for them too. Research by the funding platform Brevio estimates that UK charities spent a collective £442 million on writing funding applications during the Covid-19 pandemic, with over 50% seeing a declining success rate. With many organisations struggling to survive - ravaged by the grim ABC of Austerity, Brexit and Covid-19 - surely there’s a better way of doing things? I’m not sure it’s the done thing to write New Year's resolutions for other people, but I've been working on a 2021 wish list for trusts and foundations... Too many funders are making fundraisers' jobs harder than necessary. Not every funder is guilty - and I've tried to highlight some positive examples below too - but the vast majority could make big improvements by fixing at least some of the following: Update your reserves policy to reflect a year like no otherIf you browse what funders say about reserves levels, you’d be forgiven for thinking that keeping anything below three months or above six months of running costs is a heinous crime. It feels like organisations can’t win - step outside a narrow, arbitrarily-defined window, and you’re either financially reckless or decadent beyond belief. Yet 2020 provided a compelling justification for more generous reserves - suddenly, six months’ running costs doesn't seem so indulgent in a year-long pandemic. Equally importantly, many organisations will now have severely depleted their reserves to keep themselves afloat. So funders: it’d be great to see you reflecting on the consequences of the pandemic and adjusting your reserves requirements, at least temporarily. Adopt a two-stage application processThere’s nothing more frustrating than spending days on an application, then being told by the funder that “we don’t feel you meet our objectives” or “we're no longer funding in that area”. Even when you've researched a funder thoroughly, you often have no idea how they'll perceive your work until you’ve told them about it. That’s why it's great that funders like the National Lottery Community Fund, John Ellerman Foundation and Masonic Charitable Foundation have a two-stage process for larger grants. A simple form to gather some initial information about the organisation and project, then a longer form if they still feel you’re a potential fit. Unless somebody can give me a good reason otherwise, this is an obvious win-win. Applicants spend less time on lengthy forms that were always destined to be unsuccessful. Funders save resources too, by drastically reducing the time spent assessing so many long and unsuitable applications - this would surely more than make up for the extra administration of a two-stage process. Commit to giving feedback (at least at stage two)Getting meaningful feedback on unsuccessful applications is a game-changer for charities. If you understand why an application was rejected, you can judge whether it’s worth ever reapplying to that same funder - and use that feedback to strengthen other applications too. I get that providing feedback can be problematic for funders, particularly when they’re hugely oversubscribed. Yet this is another justification for the two-stage application process: by initially whittling down applicants to the best 10-20%, it's easier to then commit to providing feedback to those who clear the first hurdle. This seems a fair bargain to me – we might not be able to give everyone feedback but we'll at least make it a fairly quick and painless process. And if we do decide we need considerably more information from you, we’ll make sure you get something useful from it. Adopt a standardised format for common questions"Describe your organisation in 150 words" "Tell us about your aims and activities in 250 words" "How are you currently funded? (200 words)" "Briefly summarise your fundraising strategy (1,000 characters)" It's frustrating to see funders use so many variations of wording and word counts for questions that essentially want the same information, especially when it's often already publicly available anyway. Asking organisations to produce countless versions of the same description is a huge waste of time and provides next to no additional value for the funder. I get that funders will assess applications differently and need bespoke information in many areas. But for the more straightforward questions, can't you club together and adopt a standardised format? Clearly show whether you’re open to applications from new organisationsThe downside of using databases like Funds Online or Funding Central is that you turn up plenty of funders that are great on paper but will do nothing for your bank balance. Dig a little deeper (say in their annual accounts) and you realise that although their objectives seem to perfectly match yours, they haven’t given grants for two years or even funded any new organisations for a decade! These ‘zombie funders’ are a black hole of time for the uninitiated fundraiser. For example, most charities seem to have the Denise Coates Foundation on their pipeline at some point, but never receive a grant. That’s because, while it’s not explicitly said anywhere, unless you’re an organisation in the Stoke-on-Trent area that's well-known to them, you'll do just as well if you throw your application in the bin. So, funders, how about introducing a basic traffic light system on your websites and annual accounts? Red = not currently giving new grants, Amber = likely to only fund repeat applicants, Green = open to applications from new organisations. It’d save us all a lot of time. Publish some key metrics to help applicants decide whether it’s worth itWhile I’m on my soapbox about increased transparency, there are at least two other bits of data that every funder should publish: the previous success rate for applications (Tudor Trust does this here) and how long it takes organisations on average to complete an application (I know that the Postcode Community Trust used to include this on their form). This vital information would enable fundraisers to weigh up the wisdom of applying, and make funders more accountable in terms of the impact their application process has on the sector. Which leads me to… If you're going to measure your social impact, factor in the time organisations spend on failed bids to youThis won’t be popular with corporate foundations that make a big song and dance about showcasing their impact and unveiling their annual awards, but make applicants jump through a hundred hoops. On the outside, this looks great. For example, the 2020 Movement For Good awards gave away £50,000 grants to ten lucky charities whose good work is showcased here. What’s not to love? Trouble is, there was a point last summer when nearly every organisation I spoke to was applying for a grant. There was no real indication in advance of what they’d fund, the application form asked some very specific and detailed questions, and of course there was no feedback for unsuccessful applicants. Hypothetically let's say that a thousand charities each spent 1-2 days on an application - when you start to estimate the staff time involved, did this cost the sector almost as much as the amount given away? With a corporate social responsibility agenda to promote, many corporate foundations want to attract as many applicants as possible. There’s little incentive for them to ensure the application workload is proportionate to the award, and no requirement for them to measure whether they're having a net positive impact on the sector. More funders should assess this - I suspect they’d be shocked by the results. And finally, the elephant in the room…Plenty of people will say that it's entirely up to a funder how they distribute their money. What right do grantees and applicants have to intervene?

As we’ve previously argued here, there are some major issues with modern philanthropy that we absolutely have the right to challenge. Charitable status brings plenty of advantages for trusts and foundations (and their benefactors) – and the combination of tax breaks for contributing companies and Gift Aid for individual donors means that a good portion of the money they give isn’t actually theirs anyway. So, for me, the above list isn’t a list of nice-to-haves. We should put in place some clear and incentivised best practice guidelines for funders. If you want to keep benefiting from your current tax advantages, make sure you’re giving in a way that doesn’t create a nightmare for applicants. If you want to keep giving entirely on your own terms, that’s fine - but then let’s change your legal status and make sure it’s 100% your money to give. MOVING BEYOND A NICE SENTIMENT - HOW CAN WE ACTUALLY CHANGE AND CHALLENGE PROBLEMATIC PHILANTHROPY?2/9/2020

Back in June, in response to the toppling of the statue of Edward Colston in Bristol and the Black Lives Matter movement, I shared some reflections on the issues facing philanthropy.

My argument in a nutshell was this: philanthropy is inextricably tied with extreme wealth, and most of that wealth is derived from activities that increase inequality. Philanthropy gives a particular audience – wealthy, privileged, mostly white, usually male – disproportionate influence over the sector’s work and policies, and an opportunity to implement a vision of social change that is likely very different from your own. This process is inadvertently endorsed every day by fundraisers and charities – so while Edward Colston is an extreme and high-profile case, there are other examples everywhere. I’m delighted that this blog sparked plenty of debate and discussion, but I’m conscious it offered little by way of solutions. The truth is, it’s very difficult for most fundraisers to take action, especially if their organisation isn’t geared up to question philanthropy. Several people rightly asked for some thoughts on what organisations can actually do differently, rather than just why it’s important. This is where things get trickier, and more controversial, but here are my views… Reduce your long-term dependence on philanthropy

Let’s deal with the elephant in the room. It’s all very well not wanting to accept certain donations - but in the current climate, for many, it’s not unreasonable to think that turning away a big gift could lead to service closures or staff redundancies.

I can’t pretend there’s a quick or easy answer to this. But we’ve previously shared various thoughts about diversifying your income, which will inevitably reduce your reliance on a single funder, donor or income stream, and make it easier to stick to your principles. This 2018 blog explores how to build a business case to persuade your organisation to invest in developing a more diverse fundraising portfolio. And in this podcast, I interview Fran Ferris-Ockwell, former CEO of a Sheffield housing charity, on how she guided them through a process to reduce their reliance on contract income, with huge improvements to their independence and organisational culture. Most organisations won’t be able to reduce their dependence on funders and major donors overnight, but these steps are a key starting point – particularly if you're brave enough to set an explicit long-term strategic objective to become less dependent on grants and major gifts over several years. Create a fit-for-purpose ethical fundraising policy

We previously shared six guiding principles about creating an ethical policy. While it might be tempting to find a policy template online and quickly adapt it, the most important part of this exercise is having an honest and meaningful conversation with your management team and trustees. You should develop guidelines that feel appropriate for your organisation, mission and service users. Don’t expect this to be an easy exercise, or for everyone to immediately agree, as you’re dealing with a complex issue.

Be aware that enforcing your policy to the letter might lead to both accepting or rejecting donations in controversial circumstances later. This could conceivably lead to negative press coverage, complaints from supporters, disagreements with staff and trustees, or having to close a service. You need to fully anticipate and ‘test’ the potential consequences of your policy, so you can confidently justify decisions later.

Empower your fundraisers and lead by example

After publishing our original blog in June, I was contacted by several fundraisers sharing experiences where they felt uncomfortable about the ethical implications of a donation or a donor’s behaviour, but felt unable to act. For example:

Your ‘front line’ fundraisers are likely to be younger, less experienced and less influential than your donor prospects, management and trustees. They may well be working under pressure, knowing that failing to hit financial targets could well harm the organisation’s financial health, staff livelihoods and service users. So even if a fundraiser feels uncomfortable about something, voicing this might feel daunting and detrimental to their career. Solving this actually goes beyond having an ethical fundraising policy, particularly one that sits in a drawer gathering dust. Your senior management and trustees need to lead by example by openly talking about the ethical issues with philanthropy, and creating opportunities for fundraisers to raise concerns and ask questions without fearing a backlash. Something else to consider: is your approach to setting fundraising targets and KPIs creating an environment where fundraisers feel pressured to stay silent and bring in donations at all costs? Unrealistic targets - particularly those based purely on the cost of your projects rather than sector benchmark data, are another potential barrier to thoughtful and ethical fundraising. Move beyond #donorlove

This feels controversial - when I suggested this on Twitter, I was met with some incredulous responses.

#donorlove is a popular term to describe a donor-centric approach to fundraising that focuses on making donors feel loved, valued and appreciated, to encourage and retain their support. This isn’t totally without merit - many organisations don’t do this, and miss out on donations as a result. I’ve previously shared my own experiences as a donor and why charities should get better at saying thank you. But too often, #donorlove crosses into advocating putting the donor’s wishes and the importance of building a relationship with them above other concerns. I’ve seen high-profile consultants advise charities to structure annual reports entirely around recognising the contributions and achievements of the donor, even if their service users fade into the background as a result.

I think you can make a case for #donorlove being incompatible with the need to re-examine philanthropy in response to recent events - and an inadvertent endorsement of hypocritical philanthropy, the problematic influence of wealthy donors and the white saviour complex. When fundraisers are faced with the pressure of a financial crisis, silence from their senior leadership, and influential fundraisers’ unswerving commitment to #donorlove, is it really any surprise that they feel unable to do things differently?

I doubt that #donorlove is going anywhere fast - too many high-profile fundraisers and consultants have structured their livelihoods around the concept - but perhaps we need to start taking the first steps. Challenge how we structure, incentivise and culturally revere philanthropy

Philanthropy is commonly considered an unselfish, freely-taken individual act that increases equality and is open to everyone. Cast in this light, what right do we have to challenge where that money comes from, or how it is used?

Unfortunately, this view of philanthropy is false. In his book “Just Giving: Why Philanthropy Is Failing Democracy and How It Can Do Better”, Rob Reich examines the philanthropic landscape in the US and reaches two uncomfortable conclusions. Firstly, less than a third of charitable giving actually benefits low-income people. Secondly, the US tax system is massively skewed towards rewarding and incentivising the wealthiest donors: if you earn under $153,100 per year then a $100 donation costs you $100, whereas it can cost a higher earner as little as $60. Admittedly the UK landscape is somewhat different, not least because we have a Gift Aid scheme rather than just tax breaks for the donor. But essentially, the same problem exists globally: the tax system greatly subsidises charitable giving and enables richer people to donate money at less personal cost. This actually takes money out of the public purse and redirects it towards causes favoured by the rich and powerful, which rarely benefit low-income people. Philanthropy therefore can actually harm rather than help equality.

Reframing philanthropy in this way completely changes our right and obligation to challenge it. For example, how much influence and recognition should a wealthy donor enjoy for their supposedly ‘selfless’ gift? Should we permit a family trust to be opaque about where its money comes from, and how it decides which causes to support? Why can’t we create and enforce a new code of ethics and transparency, and remove the huge tax breaks for funders and donors who won’t play ball?

In barely 100 years, we’ve gone from elite-level philanthropy being met with suspicion and fierce criticism - Rob Reich documents the angry response to John Rockefeller’s early attempts to establish his charitable foundation in the US in the early 1900s - to today’s almost unquestioning endorsement of philanthropy and #donorlove. In keeping with the positive response to the toppling of Edward Colston’s statue and the Black Lives Matter movement, I think we urgently need to start nudging back in the other direction.

We published this blog in June 2020, 11 days after the statue of Edward Colston was brought down. It's now several years on, and not enough has changed...

Time will tell, but I really hope the last couple of weeks will be a landmark moment in history, with the Black Lives Matter movement gathering widespread support, and people doing some genuine, long-overdue soul-searching about racial inequality. Bristol, where I live, has felt like the epicentre of grassroots change, with the dramatic toppling of the statue of Edward Colston. Bristol is a city haunted by the slave trade, and this statue has been a focal point of the long debate about the legacy of Edward Colston. It's important to remember that the statue is very much the tip of the iceberg – at last count, Bristol ‘boasts’ eight streets, two pubs, two schools, a fruity bun and the city’s largest music venue named after Colston. Disentangling the messy web spun by such a prolific philanthropist has proved complicated, particularly as change has long been opposed by influential philanthropists in Bristol. People only took matters into their own hands after many tried - unsuccessfully - to find a democratic solution for years. This is something to be celebrated - and many have been, including the CEO of the Wolfson Foundation:

I want to agree with this sentiment, but actually I think we're at the very beginning of the argument, not the end. While few people would actively argue that philanthropy excuses the unethical practices that first generated that money, this view is inadvertently endorsed every day - and fundraisers and charities are very much complicit in this. There are examples everywhere, once you start to look.

The day after the statue came down, I felt this strange need to go down to the site myself, and just...think. I started writing this blog down there. Looming above the smashed plinth and handful of people still milling about was Colston Tower - a building that can’t be torn down by people who are fed up of waiting for official action. If Bristol wants to fully rid itself of the Colston legacy, this is going to take a conscious decision from those in power whose track record - no matter they say - still suggests they believe that philanthropic good deeds outweigh harmful past actions.

Of course, this isn't just a Bristol problem. London's Tate Galleries take their name from Henry Tate, whose company Tate & Lyle was inextricably tied with the sugar industry and the slave trade.

A great many museums have received large donations from the Sackler Trust, and some bear the Sackler name. You might well know that the Sackler Trust was closely linked to Purdue Pharma, who are accused of fuelling the US opioid crisis and spent years aggressively pursuing legal action so they could continue selling their highly addictive drugs. But we're on safer ground with most corporate foundations, right? I know countless grassroots community projects that have benefitted from grants connected to the banking sector - think Santander Foundation, the RBS Skills and Opportunities Fund, and Barclays' new 100x100 UK COVID-19 Community Relief Programme. Yet a 2018 report by Ethical Consumer magazine said this:

How many charities write ethical fundraising policies that prohibit donations from philanthropists involved in these 'problem sectors', but wouldn’t think twice about applying for a grant from a foundation connected to one of the big five banks?

The trouble is that while most people have clear views about Edward Colston, underneath this there's a huge grey area. And the more you dig, the greyer it gets.

Many social welfare charities are funded by wealthy family trusts whose trustees have, for decades, both implemented and supported policies that drive a coach and horses through social mobility. Their businesses often pay as little tax as possible and profit greatly from things like zero hours contracts - which keep vast numbers of people, including so many charity service users, locked in poverty. 2020 brought a new entrant to the UK trusts and foundations scene: the Hargreaves Foundation – founded by Peter Hargreaves, major donor to the Leave.EU Brexit campaign, friend of Jacob Rees-Mogg, and a man who outlined his employment policies and interest in charities in an interview with The Sunday Times:

And I recently discovered this remarkable exclusion from a small family trust in Oxfordshire: “We will not support charities that in our view are ambivalent about, or actively campaign for the abolition of, field sports.” Imagine being so vehemently pro-field sports that you simply wouldn’t consider funding a charity that has even mixed feelings about fox-hunting?!

Does any of this really matter? Where should we draw the line? Should we only reject money from those who have been publicly condemned for doing Very Bad Things? Or are harmful but widespread business practices up for scrutiny too? When should we take people's publicly held opinions into account - when they actively harm our beneficiaries, when they go against our charity's message, or when we just find them personally repugnant? I'm not saying everyone will take issue will all of the above examples - or that you should. But it's an important conversation to have. And I think that recent events in Bristol should mark the beginning of the argument about hypocritical philanthropy, not the end. It's an inescapable fact that philanthropy is closely tied with extreme wealth, and most of that wealth is derived from activities that increase inequality. Philanthropy often buys people 'a seat at the table', and this gives a particular audience – wealthy, privileged, mostly white, usually male – disproportionate influence to implement their own vision of equality, social mobility and climate change. A vision that is, almost certainly, very different from your own. If we want to address this, we’re going to have to start digging a lot deeper than Edward Colston. If you were asked to create an ethical fundraising policy, what would you do and where would you start? With the latest wave of bad news stories – especially the Presidents Club scandal, which saw charities scrambling to hand back donations – I’ve been contacted for advice by several organisations who, quite sensibly, want to avoid getting in a similar position themselves. An ethical fundraising policy sets out what your organisation is willing to do and not do in relation to fundraising, based on some agreed ethical principles. This often includes (but shouldn't be limited to) when you may choose to reject a donation. If this sounds like a straightforward exercise, it shouldn’t be. It goes without saying that ethics aren’t black and white, so putting together this policy must involve careful thought and reflection. Here are six guiding principles to keep in mind if you're creating an ethical fundraising policy: 1. Start a conversation - don’t search for a template policy A common mistake is to assign this task to one member of staff, and ask them to find an example policy that can be adapted quickly for your organisation. However, creating an ethical fundraising policy goes right to the heart of your appetite for risk, your charitable objects and the areas of particular sensitivity for your cause. As such, it's crucial that trustees and senior management are involved. This process should start with a conversation. This is arguably the most important stage, since you need to debate different scenarios and views, and arrive at a position that feels right for your organisation. This is usually a thought-provoking exercise that improves everybody’s understanding and appreciation of the complexities involved. If you treat creating the policy as a box-ticking exercise, you’ll miss out on this valuable development opportunity. 2. Take a broad view – don’t over-react to one event It's common to be prompted into action by a single event, like a high-profile bad news story. This isn’t a problem as such, but you shouldn't let it skew your whole approach. In the wake of the Presidents Club scandal, many charities are focused on whether they should accept (or return) certain donations. However, this is only part of the puzzle – your policy may need to cover the ethical standards you expect your suppliers to meet, how you check those standards, and how you interact with vulnerable donors. It's helpful to start by making a list of all the circumstances and ethical dilemmas your charity needs to consider. This should be informed by the types of fundraising that you do and your existing risk assessment, as well as by external events. 3. Define your attitude towards risk – avoid making decisions that you’ll reverse later Keeping everyone happy is rarely possible, as recent developments show. Many people were outraged that charities like GOSH had accepted donations from the Presidents Club, but others were reportedly angry when they considered handing them back. There are no right or wrong answers, so you need to judge what feels appropriate for your organisation, anticipate how your supporters and beneficiaries might react, and be prepared to justify your decision. It's no good having a policy in place, then caving in as soon as you put it into practice and people object. Defining your organisation’s attitude towards risk is essential – this is why trustees and management must be involved. Accepting some donations can be risky, but being totally risk-averse is a risk in itself – it can demoralise staff, or damage your financial position. This is inevitably a sensitive balancing act. It may be helpful to consult key donors and beneficiaries when creating your policy, to anticipate objections in advance. 4. Make it relevant to your cause – don’t be over-simplistic When defining whether to accept or reject donations from individuals and companies, you may be tempted to start by creating a list of 'no go' areas, like if they are linked to alcohol, drugs, gambling or pornography. Unfortunately, the world isn't that simple - household name companies sell alcoholic products, and established publishing companies produce pornographic magazines. If you're not careful, you could find yourself turning away a lot of donations! You need to be more specific and mindful of your cause and charitable aims. It's not about what staff or trustees personally think is ethically correct, but whether a donation might damage your mission or beneficiaries. An animal welfare charity might be reluctant to accept a donation from a cosmetics company, but happy to do so from an alcohol brand - whereas an addiction charity might take the opposite view. 5. Include specific processes and procedures - not just general guidelines

Your policy should not only set out your position, but explain how to action it - for example, do you subject donations over a certain amount to more rigorous background checks? What do those checks involve? How do you go about reporting serious incidents? This will help staff to put your policy into action, and also show anybody reading it that you're serious about fundraising ethically, rather than just treating it as a tickbox exercise. 6. Make your policy part of the bigger picture - don't see it as enough in isolation It's tempting to sign off your ethical fundraising policy and assume it's 'job done' - but in reality, this is an ongoing commitment and part of a larger compliance picture. Your policy shouldn't just sit in an obscure corner of your shared drive. It must be an ongoing reference point that's displayed clearly for staff to refer to when needed, and part of induction processes for staff and volunteers. Fundraisers should feel able to raise any concerns or discuss situations they feel unsure about. Management and trustees should review your policy periodically, in response to changing fundraising practices, issues affecting the sector, and changes to your own fundraising portfolio and risk assessment. Aside from creating an ethical fundraising policy, you may also want to, for example, review your Data Protection compliance ahead of the arrival of GDPR, ensure your trustees are aware of their legal fundraising duties as set out in the Charity Commission's CC20 document, or produce a short supporter promise outlining your commitment to good fundraising (I've always liked this example from Mind). |

Like this blog? If so then please...

Categories

All

Archive

May 2024

|

Lime Green Consulting is the trading name of Lime Green Consulting & Training Ltd (registered company number 12056332)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed