|

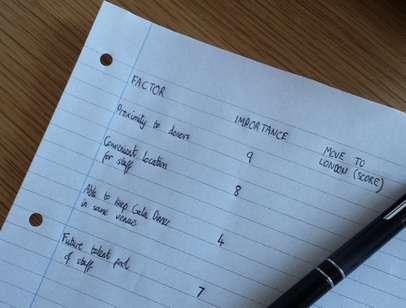

Last month my girlfriend and I decided to liven up our lives by adopting two kittens from a rescue centre in East London. We called them Rupert and Jasmin and they’ve settled in brilliantly – but there’s a small problem. It’s not scratch marks in the sofa or even the time that one kitten started playing manically with a jingly ball during an important conference call. No, it’s all in the names. You see, based on our poor judgement and some questionable advice from the rescue centre, we got the kittens the wrong way round when naming them. We now have an adorable little girl called Rupert and an inexplicably angry young male called Jasmin. The connection with charities and fundraising seems tenuous, but there is a useful lesson in this. Making key decisions can be difficult, particularly when you don’t have a process in place to help you get them right. For small charities, all kinds of decisions can be difficult to make and fraught with anxiety. Whether you’re considering relocating to a new office, recruiting a fundraiser or deciding which potential income stream to invest in, the stakes can be high. If you don’t have large reserves and you get a critical decision wrong, you may put the survival of the organisation in jeopardy. So there’s a natural tendency to be risk-averse. On top of that, many charities lack in-house strategic expertise. Of course, Trustees are there to help – but put yourself in their shoes for a moment. As I know myself, being a Trustee means that you are legally accountable for the decisions you make. Yet you will receive no financial rewards for making the right call, however strategically brilliant it is. Try putting most people in that position and see if they’ve got any hunger to stick their necks out and take risks. Alex Swallow, former Chief Executive of the Small Charities Coalition and Programme Director of the Charity Leaders' Exchange, is a real authority on this subject. He told me that “smaller charities are often grappling with a number of options which can seem mutually incompatible. “Things like wanting to get the best person for a role, while knowing they can't pay the best price. Or wanting to bring in specialists, while knowing that there is so much to do that everyone needs to be a generalist. Or wanting to grow the charity to safeguard the future, when the risk is that making the investment to do that could put the charity in jeopardy. “In this context, having a good strategic plan to follow and the tools to make strategic decisions on a daily basis are crucial.” I would recommend three things to help you make better and more confident decisions: 1. Involve the right people – building a strong and diverse Board means that you can call on a range of different perspectives. Don’t just recruit people who know the cause well – strong leaders from all fields and those who bring commercial experience are crucial. 2. Do your research and base your decisions on sound knowledge. Who are the experts in the area and what do they say? What have other charities done in similar circumstances? Often others have done a lot of the hard work for you. For instance, if you’re writing a fundraising strategy, you absolutely must read a paper called Gimme Gimme Gimme by nfpSynergy. It’s a brilliant introduction to some key principles of fundraising and the different fundraising opportunities that may be open to your organisation. 3. Approach the process methodically – key decisions shouldn’t be evaluated emotionally or dictated by the person who puts their point across most forcefully. Valuable insight can come from many different voices and there are some established processes and tools out there to help you harness this. With this in mind, I’d like to introduce you to something called Operational Research. Piers Horner is a professional Operational Research analyst who makes a living analysing data and developing processes so that organisations can make smarter and more effective decisions. He believes that a lot of the tools used in his line of work could make an enormous difference to the small charity sector. Piers explains: “Operational Research is often referred to as ‘the science of decision-making’. On a strategic level, it provides approaches to coping with complicated or 'messy' decisions. “This can help you to understand your customers or stakeholders better and ensure their buy-in to crucial decisions. It encourages you to ensure that you factor in the widest possible range of cross-cutting issues to your thinking. This can often help you to identify counter-intuitive solutions to strategic problems. "Put simply, Operational Research gives you more control over strategic decision-making.” Let’s look at a practical example of this in action. Imagine that your charity is weighing up a potential relocation. It was founded in Suffolk and opened an office there because it was convenient for the first members of staff. It has now grown substantially, needs bigger premises and is considering a permanent move to London. There are potentially many advantages to moving, including access to a bigger talent pool of potential staff and the ability to meet more frequently with key funders and donors. There are also disadvantages – rent would be much more expensive, and current staff would find it difficult to keep their jobs. It’s an incredibly important and difficult decision to make. Everybody understands the broad reasons for and against the move, but they all have different priorities and emotions are involved – inevitably so, because people’s livelihoods are at stake. Arguments are just around the corner and there is a risk that the loudest voices will end up deciding what happens. This could be avoided if you use something called MDCA – Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis. It’s much more exciting than it sounds! Senior staff begin by making a list of all the possible criteria that should be considered when making the decision. They discuss each one and, as a group, give it a weighting score based on how important it is to the overall picture. This provides a sound platform for the decision they need to make. Next they weigh up the two possible choices (moving to London or staying in Suffolk) against the agreed criteria, giving each choice a score. In theory, calculating all the scores and weightings will show what is the best decision. However, this isn’t the end of the process. People may be surprised by the results and, in the process of scoring the decisions, they may realise that some criteria are more or less important than they thought. They can now revisit the criteria, re-run the scoring process and bingo – they have a result. If this all sounds very scientific, that’s because it is.

Approaching decisions in this way has several advantages. It allows people to identify the factors are important to them, discuss them openly and understand how they affect the final decision in a very transparent way. This often helps people to realise if they are arguing something from one entrenched point of view without considering other perspectives. The final decision may not be a perfect choice for everyone, but it will be the best possible compromise. Those involved will appreciate the fair and logical process and will be much more likely to support and engage with the decision taken. This is just one of several established techniques that can replace anxiety and controversy with logic and confidence in your strategic discussions. In the interests of time, it’s the only example I’ve included here! I’ve been working with Piers to explore how Operational Research techniques can be applied for charities. This is particularly relevant when it comes to fundraising strategy. I’ve seen many charities begin the process of developing a fundraising strategy by writing a SWOT analysis. It’s a great way to examine what you do well, where you struggle and where there are future opportunities and risks. Often charities do this well but the process goes no further. When you read the final strategy, too many of the key opportunities and risks have not been addressed. Operational Research techniques can be used to ensure that all those involved in developing a fundraising strategy keep ‘the bigger picture’ in mind every step of the way. Your final strategy should be more than a list of ideas and plans. It must be the blueprint to address the challenges you need to face. I’ll soon be adding some free resources to my website to help you apply some of these techniques. I can also run workshops to help you develop your approach to strategic planning or to evaluate one key strategic decision. Knowing about the processes I've mentioned above is a great starting point, but to get the most value out of Operational Research it really helps to have an independent 'facilitator' who is experienced in applying them. I’d love to discuss this with you so please get in touch if you think I can help. And in case you were wondering, our biggest ‘strategic dilemma’ at home remains unresolved. Fortunately our poor kittens seem blissfully unaware of their naming crisis. Piers hasn’t yet suggested an Operational Research technique to help with that. So if this blog has been helpful and you would like to return the favour, please leave a suggestion below!

6 Comments

Sally

23/10/2014 07:32:01 am

Very thought provoking - good tips for problem solving, whether you're in the charity sector or not!

Reply

29/10/2014 05:26:27 am

Thanks Sally - glad you found it useful and thought-provoking!

Reply

Luke

23/10/2014 09:26:19 am

As a charity trustee, I've just learnt that I am legally accountable for the decisions I take.

Reply

29/10/2014 05:29:52 am

Well that's a good starting point I guess Luke! There's an excellent guide to being a Trustee on the Government website which you might find useful:

Reply

Jon T

24/10/2014 03:14:14 am

Excellent article. There are a number of good analytical tools and techniques that can help decision makers to quantify benefits and costs - and SWOT/MCDA are a couple of great examples. A lot of the value can come through these (or similar) processes and looking at a problem in an analytical rather than biased way. If these exercises are set up correctly then they can reveal some unexpected and useful insights. One of the real challenges is how to strike the right balance between intuition and analysis, and another is how to convince the decision makers about the value of going through these (sometimes quite lengthy) exercises.

Reply

29/10/2014 05:33:49 am

Thanks Jon and I really appreciate the feedback and thoughts.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Like this blog? If so then please...

Categories

All

Archive

May 2024

|

Lime Green Consulting is the trading name of Lime Green Consulting & Training Ltd (registered company number 12056332)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed