10 years of Lime Green Consulting - and 10 top fundraising and strategy lessons that we've learned11/7/2024 10 years ago this month, I launched Lime Green Consulting - with a simple, on-a-shoestring website and a half-formed aspiration to help smaller charities navigate their way through a challenging landscape. I’d been freelancing for a few months, having previously been Fundraising Manager at a small international development charity. I wanted to help people wrestling with some recurring challenges: the pressure to sustain income in a tough funding climate, the need for a really focused strategy, and the challenge of delivering results with a limited budget, risk-averse Board and small supporter base. To be honest, we spent most of the first two years figuring out what type of support we wanted to provide, how to explain it, who we wanted to work with, and how to reach them. There were times when I wasn’t sure I could find enough work to keep me busy, let alone the team we’ve become. In a classic freelancing tale, those worries quickly flipped to trying to figure out how to keep on top of multiple projects without the need to still have my laptop open at 9pm. It truly is a rollercoaster ride. 10 years later, we've provided consultancy support to over 350 charities and social enterprises, trained well over 2,000 people, and raised millions of pounds of vital grant funding. All against a backdrop of the greatest turbulence the sector has ever known – we've worked through six Prime Ministers, the worst of austerity, Brexit, a global pandemic and now the cost-of-living crisis. This has been bittersweet - on the one hand, it’s been a privilege to help people navigate their way through the uncertainty. On the other hand, it’s frustrating knowing that if only other people (Government, commissioners, funders) could get their sh*t together, maybe we - and many of the charities we’ve supported - wouldn’t be needed at all. I wanted to mark our 10th anniversary in some way, but I had the words of a very wise fundraiser ringing in my ears – anniversaries very rarely mean much to people outside your organisation, so don’t go overboard, and have a clear purpose in mind. So we've kept things simple and just taken the opportunity to re-share 10 of our biggest lessons from a decade of running Lime Green. These are all things that we’ve written about before, but keep coming back to in our training courses and consultancy work. Enjoy the recap... 1. Don’t invest time in creating a strategy that ends up in a dusty drawerA good strategy takes lots of time, lots of people, lots of planning. Done right, this can bring about much-needed clarity and confidence in the future. But there’s nothing more dispiriting that all that energy ending up in a lengthy document that nobody ever reads or refers to, and doesn’t change or guide people’s day-to-day work. You can partly avoid this by designing a collaborative and inclusive strategic planning process, but there are also plenty of things you can do after writing up your strategy to ensure that all the hard work is worth it. 2. You’ll never get anywhere without a fundraising-friendly cultureYou may have talented fundraisers, money to invest, and a good case for support. But if you don’t have a fundraising-friendly culture, you’ll still fall way short of your potential. For me, a fundraising-friendly culture is when everyone in your organisation - whether that’s five, 50 or 500 people - recognises the importance of good fundraising to the bigger picture of your work, understands all the little things they can do to support your fundraising efforts, and feels motivated to play a part. Here’s a list of the key things that all the best fundraising charities do and have in place. 3. If you’re starting public fundraising from scratch, people knowing you’re a charity is half the battleWe work with a lot of organisations that are looking to become a true “fundraising charity” for the first time, often prompted by the loss of a key statutory contract, or dwindling grant funding. Yes, they need to think about fundraising tactics - appeal themes, regular giving schemes, suggested donation amounts. But first and foremost, they need people to appreciate that they’re a charity in need to donations, in a world where few people have any real understanding of how many vital organisations are charities, and how they’re funded. We’ve previously shared these thoughts on how to ensure people know you're a charity, and why this is so important. 4. When in doubt, fall back on some universal fundraising truthsWhen the pandemic first hit in early 2020, we scrambled to help smaller charities that had been thrown into crisis. We organised several free online Q&As, fielding a wide variety of questions on how to respond and how to adjust fundraising tactics. Hopefully we provided some inventive advice - but you know what, we mainly realised that when the world gets turned upside down, it’s the same universal principles that will get you through. Careful prioritisation, building on your strengths, investing time in donor relationships, saying thank you well etc. This prompted us to write up seven universal fundraising truths that will never let you down – and four years on, we still swear by them. 5. Invitation-only funders offer untapped potential, if you know how to engage themEver found a funder that seems like the perfect fit, only to learn they don’t accept unsolicited applications? It’s easy to write off these funders with a sinking feeling, but if your work is niche and/or you’ve approached all the ‘obvious’ household name funders already, then invitation-only funders may hold the key to broadening your funding base. Over the years, we’ve sussed out some of the main reasons why funders go down the invitation-only route, and how you can build relationships with them. And it’s been encouraging to get feedback not only from charities that have successfully put these tips into action, but also from some funders saying this is how they like to engage with new organisations too. 6. There’s no getting around it - trusts fundraisers need to pick up the phoneFor many trusts fundraisers, getting on the phone to funders is one of the least enjoyable parts of the job - but it can really help. Sure, we’d all prefer to live in a world where funders’ online guidance is crystal clear, and their decision-making processes are completely transparent, meaning a quick phone call wouldn’t be needed or have any impact on our prospects. But we don’t. Over the years, I’ve received so many nuggets of information from funders over the phone, in the form of helpful advice or telling throwaway comments. This prompted us to share some tips on good questions to ask as a reason to phone a funder in the first place, and further information to probe for once you’re connected to them. 7. The best trusts fundraisers ask difficult questions, instead of papering over the cracksOne more underrated skill in the trusts fundraising toolbox before we move on: the ability to ask difficult questions internally. I’ve found that while most charity staff will be hoping you’ll write applications as quickly as possible, and use your own initiative to fill in the gaps, there’s often good reason for slowing things down. Spotted a gap or contradiction in your organisation’s consultation data, project activity plan or budget? Struggling to explain a point that feels key to your application? Don’t plough on regardless - it's your job to anticipate and address any concerns a funder might have, not to work as quickly as possible and keep colleagues happy at all costs. 8. Unless and until funders change, we can’t get anywhere as a sectorDespite all the tips above, good trusts fundraising tactics will only get us so far. Because it’s also the job of funders to make it easier to understand them and access their grants. They should see this as both a moral responsibility and one of the best ways of increasing their social impact. More core funding. More straightforward and accessible application processes. Clearer guidelines and more flexible funding criteria. The best and most progressive funders are nudging in this direction, but many more need to follow. Because bad grantmaking does our sector no favours, and it has a human cost too. As a fundraiser, you’re not totally powerless - take the opportunity to call out bad grantmaking practice, and support brilliant initiatives to change the sector for the better when you see them. 9. Philanthropy is problematic, and you need an ethical fundraising policy to get through this minefieldRecent years have brought some clear-cut examples of “bad money”, including Edward Colston and the Sackler Trust. But dig a little deeper, and there are countless grey areas to contend with. The fundamental problem is that philanthropy buys a seat at the table for a very specific demographic - wealthy, privileged, usually white and male. Through their decisions on what they do/don't fund, their roles on Boards and advisory groups, and their status as thought leaders, they gain disproportionate influence in implementing their own vision of social change and climate justice - and that vision may be very different from your own. Navigating your way through this, and deciding when to accept or reject a donation, isn’t easy - especially at a time when funding is so precarious. You’ll need an ethical fundraising policy – and this means having challenging but empowering conversations with people at all levels of your organisation, rather than quickly downloading and filling in a template policy. 10. The small charity sector needs consistent, quality, well-funded infrastructure supportIn the past 10 years, we’ve worked with so many brilliant small charities run by people who haven’t had the luxury of professional training, have little money for skills development, and may not speak English as a first language. They do incredible work but they have so many hurdles to clear - for example bid writing, finance, and IT - all without the budget to recruit a specialist staff member or consultant. They need prompt, dependable, consistent infrastructure support wherever they are in the country. And right now they're not getting it, following the closure of multiple national infrastructure organisations in recent years. This is partly down to a collective failure by grantmakers - resulting from short-sighted policy and excessive ego - and we’ll keep banging this drum until things change. A heartfelt thanks to each and every one of you that we’ve had the pleasure and privilege of working with since 2014. And here's to the next 10 years, hopefully in a less turbulent landscape and under a more positive Government 🍾

0 Comments

Many fundraisers and small charity leaders that I speak to are under pressure to close a significant funding gap or meet a daunting fundraising target this year. This feels natural, especially in the current climate. But it's also likely to be holding back your growth potential. What if I told you that raising less money this year might be the smartest thing your organisation could do? When we're under pressure to raise funds quickly, we turn to tried-and-tested tactics. Such as writing a few more funding applications. Or searching for opportunities to secure another local authority contract. These tactics, when successful, give trustees and management a sense of security and progress - an extra zero on a financial report, a new project launched, a new staff member recruited. But how much security and progress does this really bring? By the following year, you're back in the same position, needing to close the same funding gap to avoid scaling back. Running to stand still. Having to work just as hard to raise the same amount, if not harder given the ever-increasing competition for funding. No breathing room or flexibility to respond to unexpected events or costs. It doesn't always have to be like this. Some income streams offer you the prospect of a higher return on investment, more flexibility and more security further down the line, if you take action now and can get that far. When we’re working with a charity or social enterprise on their fundraising strategy, we always encourage them to cast the net a bit wider and consider the potential of other income streams that aren’t immediately on their radar. Two income streams in particular. Regular giving and legacy fundraising - what are the benefits?Regular giving can be tricky and slow to grow, and may require a culture change if you've only ever previously relied on grants. But long-term, the return on investment can be significant, and the benefits huge. It generates unrestricted income that you can spend as you wish. Also, dependable income: if you start a financial year with 100 direct debits, you can be pretty confident of broadly how much you’ll raise and when, which is great for cash flow and financial planning. Plus regular giving is a great springboard for other opportunities: people who donate regularly and are engaged in your work may shout about you to others, unlock corporate fundraising opportunities with their employer, or become future major donor or legacy prospects. Legacy fundraising, while similarly slow to develop, potentially has an enormous long-term return on investment, partly because there’s very little to actually spend money on - just a small up-front investment in some resources and strong messaging to drip-feed to your supporters via email, social media etc. A very small outlay may bring a game-changing windfall down the line. I’ll never forget visiting a family centre in Gloucestershire the day they’d been contacted by a solicitor to notify them of a forthcoming unrestricted donation of £150,000 - a former service user had sadly passed away and generously promised them a percentage of the proceeds of their house sale. A joyful moment and totally transformative for their future work. Given this potential, why don't more organisations take the plunge and invest in long-term income streams?Firstly, there are a couple of good reasons. Some organisations are fighting to keep their doors open in a thankless financial climate, and simply don’t have any possibility of waiting for a return a few years down the line. Others are operating in a disadvantaged local community where these income streams simply aren’t a good fit, because they have little or no opportunity to reach people with the ability to donate. However, other organisations have somewhat understandable, but much less justifiable, reasons for writing off these income streams:

This last point is a really crucial one. In trying to steer away from activities that risk not raising as much as hoped, many organisations steer into the greatest risk of all: becoming over-reliant on ‘safe’ income streams that gradually dry up over time, then hitting serious financial difficulties because it’s too late to react and try something new. I often use a plane analogy here. If you were flying a plane that you knew was steadily running out of fuel, the risk of attempting an emergency landing might feel daunting. In different circumstances, you wouldn’t dream of trying it. But the alternative option - carrying on flying and running out of fuel mid-air - is actually guaranteed to fail. So an emergency landing, while more drastic, is comparatively lower-risk. In conclusion - invest if you possibly canIt’s true that many organisations aren’t in a position to easily invest in high-potential, slow-burn activities like regular giving and legacy fundraising. But this isn't an issue with the income streams themselves. The problem might be that nobody took the plunge and invested in them ten years ago.

If your organisation does have a comfortable level of reserves, or can otherwise take action to create some breathing space, I’d strongly recommend exploring how you can diversify your fundraising activity and invest in long-term growth activities. In 5-10 years, you’ll likely be extremely grateful for it. Even if that means raising less money this year, it could be the best decision that you ever make. You've just finished drafting an important funding application and you're confident that it sounds clear, compelling and unique. Now, imagine that it'll be the 25th application that the funder has read that day. Many of them relate to the same community or cause area. All have been written by people working in the same sector, where organisations often use the same language to describe their work day in, day out. Still confident? I spend a lot of time reviewing draft funding applications written by charities and social enterprises, and it's amazing how often the same phrases crop up. Our work is innovative, high-impact, urgently needed. We have strong leadership, we're financially well-run, we're responsive and shaped by lived experience. Etc etc etc. And it's hard to be critical, because often these things are true for the organisation that we're working with. The problem is that most organisations naturally want to say the same thing, whether they can back it up or not (and let’s face it - this is partly because funders often repeat the same words too, and are pretty unoriginal about what they’re looking for). So the same words and phrases pop up again and again in funding applications, until they essentially become meaningless. Your application might not be inaccurate or untruthful, it’s just the victim of over-used language that doesn't really earn anyone any credit these days. I often find myself giving similar feedback on draft applications: “I’m sure this is true, but can you actually demonstrate how?” Showing - as opposed to telling - is often key to writing a more impactful funding application. Can you find more authentic, original ways of saying what everyone else is saying, and demonstrating that they’re true? I’ve shared some of the most common fundraising application cliches below, with some tips on how to avoid them: Don't tell me that your work is innovativeShow me which aspects of your work are genuinely unique and ground-breaking:

Often, when organisations describe their work as innovative, they just mean that it’s a bit different and better than other services available locally, or they’re not personally aware of anyone else following the same approach. So do your research, and ideally steer clear of using the word ‘innovative’ at all. Seriously. This one was the inspiration for the whole blog. Don’t tell me that your work is co-produced or shaped by lived experienceShow me your track record of involving people who use your services, and people with lived experience, in designing your activities, in genuine and meaningful ways:

Don’t tell me that your organisation has been running since 1963 and has a long track record of successful service deliveryShow me what makes your organisation particularly well-placed to achieve future impact and be a “safe pair of hands” for a funder:

Don’t tell me that your work is high-impactShow me the power and scale of your organisation’s impact through:

Don’t tell me that there’s an urgent need for your workShow me what that need actually looks like, and how you know it exists, for example by referencing:

Don’t tell me that your organisation has strong leadershipShow me who is actually involved in running your organisation and why this should give a funder confidence. For example:

Don’t tell me that you’re financially well-runShow me that you've got the necessary financial expertise and focus by:

While word counts in most funding applications are tight, hopefully the above tips will help you to avoid the most common cliches and make a clearer case for why you're a credible organisation, doing compelling work. Good luck!

It takes a lot of different things to ensure that fundraising is successful in an organisation: talented people, adequate budget, a convincing case for support and often a drop of good luck. But there’s something else that too often gets overlooked: organisational culture. During our training courses and strategic planning work, we talk a lot about the importance of having a whole-organisation approach to fundraising and a fundraising-friendly culture - but it can be difficult to explain what this really means. For me, a fundraising-friendly culture is when everyone in your organisation - whether that’s five, 50 or 500 people - recognises the importance of good fundraising to the bigger picture of your work, understands all the little things they can do to support your fundraising efforts, and feels motivated to play a part. So what are some of the features of a fundraising-friendly culture in a charity?This isn't an exhaustive list but, in my experience, the best fundraising organisations always:

🎉 Celebrate success - it’s a really tough time for fundraisers currently. We're burnt out, under pressure due to unhealthy levels of scarcity and competition, and we hear no a lot more than we hear yes - even when we're doing a good job. Added to that, people often seem to take more interest in our work when it’s underperforming, but simply move the spotlight to something else when it’s going well. So when that big grant success comes in or an event smashes expectations, shout about it internally – it’s quick, easy, free and makes a world of difference. 💭 Allow space for reflection - under pressure to deliver, fundraisers rush from activity to activity. It’s often straight onto the next thing in the diary or on the to-do list, leaving little or no time to reflect on what went well and how to improve things next time. Good fundraising organisations encourage their people to stop and think – and join in that process constructively – whether that’s through formal evaluation or just allowing a little room to breathe. The best planning and debriefing meetings raise more money indirectly than most activities! 🎯 Set sensible targets - there are a lot of negative associations with the word “targets”, but they can actually be very helpful in providing structure to staff, who may not otherwise know whether they’re doing a good job. However, targets need to be realistic, evidence-based and planned in collaboration with your fundraising team. If they’re imposed on people from above without any context or discussion, this breeds resentment and pressure. 👨👩👧👧 Involve and engage everyone in fundraising - your whole team (including staff, trustees and volunteers) have a role to play, but it’s important to reassure them that this doesn’t mean making the ask, shaking a tin, or doing anything that makes them feel uncomfortable. Instead, they can supercharge your fundraising by providing data, sharing updates, making introductions and contributing ideas - but they need to know this and feel encouraged to help. 💥 Strive to articulate human, person-centred impact - there's no getting away from the fact that funders and donors love to understand the impact of their support. The best organisations try to meet this need, while understanding the challenges involved. They're humble, shifting the emphasis away from their own work and onto the stories of the people involved and lives changed. They're curious, taking extra steps to articulate the real human impact of their work, rather than using abstract concepts like 'reducing isolation'. They're respectful, working with frontline staff and service users to measure impact in more natural, less intrusive ways and focus on empowering messaging and positive imagery. 💷 Invest in fundraising - even if you have the very best fundraiser and most compelling cause, you can’t magic up results unless you’re willing and able to put in place the required capacity, expertise and supporting resources. All your fundraising activity should start with an honest conversation about what it will take to produce and sustain results. Keep your expectations in proportion to your investment - if you can't invest properly in everything, narrow your focus to fewer activities that you can do well, and avoid spreading yourself too thin. 🧠 Trust the experts - good fundraisers have been doing things for a long time and have an instinctive feel for what a realistic return looks like and what they need to succeed. It can be dispiriting and counter-productive to undermine that experience because someone is trying to push through an idea that they personally think is brilliant, or has worked in a completely different context, but which isn't a good fit for your own carefully-crafted strategy. So when your fundraiser tells you that writing to Bill Gates or planning a golf day aren’t a good use of their time, please try to listen! ⚠️ Balance risk and innovation - that said, some ideas are worth trying, even if they’re not guaranteed to succeed. Fundraising innovation and growth are vital, but can be all too easily be stifled when people are excessively risk-averse. By all means question a new fundraising idea and do your due diligence. But remember that often the biggest risk isn't trying something new, but doing nothing new for 10 years and watching your 'safe' income streams dry up until it's too late to replace them. We've written more on balancing risk and reward here. ❤️ Value donors - donors are people, not cash cows, but it’s too easy to inadvertently treat them as the latter when you’re short on time and money. This is a fundraising topic as old as time, and we don’t have much to add, but the best fundraising charities take time to say thank you brilliantly, prioritise building relationships and learn what makes their donors tick. It’s the right thing to do, it benefits the whole sector, and the money will almost always follow. But wait, there's a caveat… ⚖️ Embed an ethical approach - sources of funding are complicated, donor behaviour is often far from perfect, and there are huge power imbalances in our sector. So let’s be clear: valuing your donors doesn't mean putting them on a pedestal, condoning everything they do, and shying away from challenging them when needed. While the obvious answer is to create an ethical fundraising policy, this is only part of the puzzle, and never works well as a tick-box exercise. If you want to tread a truly ethical path through a minefield of nuanced issues, you need to empower your team to debate some tricky decisions and feel comfortable to raise concerns when needed. What have we missed? What would you add to this list, based on what your organisation does well or what you've seen someone else do brilliantly? Let us know in the comments below ⬇️ GEARING UP FOR A GENERAL ELECTION - HOW CAN CHARITIES MOBILISE TO CREATE THE CHANGE WE NEED TO SEE?11/1/2024 If you could have one thing in 2024, what would it be? Very high on my list is a General Election and a change of Government, as soon as possible. With an Autumn Election currently looking most likely (assuming we believe that Rishi Sunak is telling the truth *cough cough*), it’s time for the charity sector to start mobilising and planning what we can do to bring about the change we need. Having worked in the charity sector throughout 13 years of austerity, I’m unlikely to be a fan of any Tory Government. Even so, this is a Government like no other - looking beyond ideology and policy, we're being governed by a bunch of nasty, self-serving, talentless political vandals who have heaped never-ending misery on the most vulnerable people in society, as part of their increasing desperate bid to stay in power. This summary barely scratches the surface, but we have seen them:

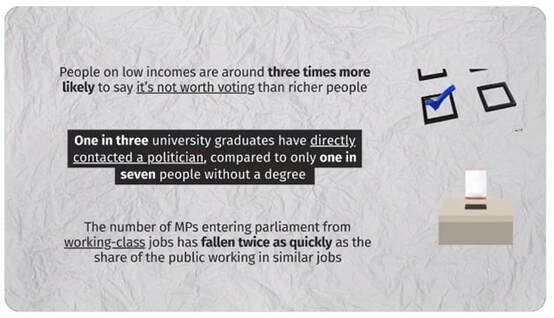

Sometimes you have to pause the remember the sheer scale of the damage that's been done, because it's been going on for so long that there's a risk of becoming desensitised. And now we have a rare chance to reject the cruelty and political vandalism. As charities and charity sector professionals, we often feel hopeless and helpless about the state of the world and the plight of the people we care about. But 2024 will bring a precious opportunity to make a difference. It’s the first time in my adult life where it feels like there’s a genuine prospect of a swing away from a Tory Government. And frankly, if we're not making that a priority, what else are we doing with our time that's going to have a bigger long-term impact? So this blog is a rallying call to everyone in the sector that I’ve ever worked with - let’s build our belief that we can bring about change, and start sharing ideas about how. Firstly, two important caveats...One: I’m under no illusions that a different Government will fix everything. While conventional wisdom says Labour are the only electable alternative, I dislike a lot of what Keir Starmer says - in many policy areas, Labour are uncomfortably similar to the Tories. But while a Labour Government won’t change nearly enough - at least in the short term - it should immediately mean less incompetence, corruption and dog-whistling cruelty. If achieving real social change is like running a marathon, then a Labour Government equates at the very least to buying a pair of reasonably-fitting running trainers – a small, but vital, first step. Two: I know that many charities are understandably nervous about any form of campaigning or perceived political activity. It's worth noting that new Charity Commission guidance says that “Charities can take part in political activity provided it supports their purpose and is in their best interests” - but political activity can’t become the reason for your existence, and you mustn’t give your support to a political party. Electoral law also requires charities to monitor and in some cases register how much they spend on specific regulated campaign activities. There are other requirements too. If you're a registered charity, you should absolutely familiarise yourself with this guidance, but it shouldn't deter you from being active and vocal. There’s loads that we all can and should do this year - and it's primarily about promoting healthy democracy, and empowering people who rarely have a voice, not supporting any particular political party. It just so happens that it's also likely to help bring about the change that we so desperately need. Gearing up for a General Election - five things we can be doing as charities and social enterprises1. Encourage people to go out and voteA new report from the charity and progressive think tank IPPR highlights the alarming gap in political engagement between different socioeconomic groups. Wealthy people, homeowners and graduates are far more likely to vote and engage in politics - this has huge implications for democracy and tackling inequality. So encouraging and empowering your service users to simply go out and vote - even if you say or do nothing else - will change Election results and challenge the status quo. Your organisation is ideally placed to do this - the people you support already know you and trust your frontline staff. So you could:

Lloyds Bank Foundation published this guide for small charities ahead of last year’s local elections, including some very helpful tips on how to support people to vote. 2. Engage your service users and supporters around key policy issuesBrexit showed us that there can be a huge and problematic gulf between the views of a charity's leadership and its service users. While organisations planned for and talked with confidence about a Remain outcome, many of the vulnerable and politically disengaged people they supported were being seduced by Leave campaign promises. My impression is that most charities spent little time bringing people together to discuss and learn from each other's views. In hindsight, this was a mistake and a missed opportunity. Ahead of a General Election, we need to learn from this and get a lot more vocal about engaging our own audiences. Your service users will very likely be impacted by the Election outcome and the headline policies that will form part of the political parties’ campaigns. You should look for opportunities to link key policy debates with the real-life issues that your service users are facing, and the causes that inspire your supporters. This isn’t about telling people how to vote, but making their vote feel more relevant, important and impactful. For example, you could do this by writing blogs, sharing relevant petitions, or linking to articles and reports on social media. Even the smallest charity has the power to reach and engage someone new - and for every organisation that stays silent, an opportunity is missed. 3. Combat disinformationThere’s going to be a LOT of disinformation circulating ahead of this Election. Meat taxes and “illustrative” northern infrastructure projects, anyone? Beyond the usual bare-faced lying, expect deepfake technology to be a new battleground: videos appearing of people saying things they never actually said, and even people casting doubt that things they did actually say were deepfaked. Sound confusing? It will be, and there are growing fears that we’re not ready for it. Every charity can play a simple role in combatting disinformation and amplifying truth. This might involve linking to relevant fact-checking sites, drawing on your own expertise to show why policy promises won’t work, and sharing warnings about deepfakes. As another helpful tool, Twitter (still not calling it X) now has a “community notes” function to provide context on misleading tweets, for example: 4. Add your voice to those championing the sectorCharities should have a vital role to play in shaping policy - they work closely with society’s most vulnerable people, their frontline work means they understand community and healthcare settings better than most, and they’re usually the first ones on the scene when society’s safety net fails those in need. Yet charities - and by extension lived experience - have been repeatedly ignored and marginalised by this Government. And when it occasionally remembers they're here, it’s usually to criticise or disempower them - for example threatening to fine them for helping homeless people, or cooking up fake controversies about donation acceptance policies. A General Election brings the possibility of a new Government that might work more constructively with the sector. More immediately, there's an opportunity to encourage all political parties to listen to charities and factor in their needs and views as they shape their election promises. This helps to gradually shift the Overton Window and change what matters to people and what gets talked about. Achieving this takes a coordinated effort - we all need to take opportunities to contribute our ideas and voice. For example, NCVO has published a draft Charity Sector Election Manifesto with five key themes, and you can share your feedback and ideas until mid-February. Local sector infrastructure organisations will be doing their own consultation. Your contribution will help to ensure that our sector is more representative of everybody, and enjoys a higher profile ahead of the Election. 5. Factor a change of Government into your strategic planningFinally, if you’re planning a new strategy this year, be sure to think ahead to what a change of Government (or simply a change of local MP) might mean for your organisation.

What potential policy changes do you want to be ready to capitalise on or challenge? Which aspects of your work might become harder or easier? Who do you need to be building relationships now as their influence grows - and similarly, what connections do you stand to lose and how might you compensate for that? This final point isn't related to the Election itself, but will ensure you’re ready to take advantage when change does come. Because finally - and with your help - hopefully we can look forward to more than just the status quo in 2024. This is a guest blog from Gemma Pettman. Gemma has been involved in running our fundraising training courses for the past six years (time flies!) so we're delighted that she agreed to share some of her top tips from these sessions in the Lime Green blog. According to research carried out by the Association of Charitable Foundations, grant-making grew to £3.7bn in 2020-21, a new high for the sector. But while grant-makers are giving away more money than ever before, competition for funding remains fierce. We can assume a significant proportion of this total was allocated to organisations who applied via formal grants programmes, which gets you thinking about how many of us are writing funding bids at any one time. A lot is riding on the strength of our applications. We need to know our organisations and individual projects or services inside out. We must be able to speak confidently about the people we support and how this grant will make a practical difference. We need detailed budgets - and the ability to explain them. And we need to wrap all of this up in a way that meet the funder’s needs and demonstrates how, by backing us, they can meet their own charitable purpose. With all of these requirements, is it any wonder our first drafts can end up a little dry? Given tight word counts and even tighter deadlines, is there any point in adding some sparkle to our funding applications? Do we need to worry about our use of language or achieving grammatical completeness? I think so. Put yourself in the shoes of the person assessing your grant. They pick up the 26th application they have read that month, and it captures their attention from the first paragraph. It offers a compelling ask, backed up by some carefully chosen statistics, and paints a strong picture of the impact the grant could have. Now, I’m not suggesting wordplay alone is enough to secure funding, but it could certainly help your application to stand out and be memorable. Writing skills are something I focus on when I’m delivering Lime Green’s Writing a Successful Funding Application short course and I’ve summarised some of the tips we share below. These are offered with the caveat that, first and foremost, you should follow the funder’s instructions to the letter. Whatever advice appears in their application criteria trumps the guidance we’re offering here. Think of these as general tips you can apply as and when appropriate. 1. Answer the question!Perhaps the most obvious advice but it is very easy to write what you want the funder to know, rather than responding with the information they have asked for. Try also to avoid getting lost in the detail. Often there is only room for your headlines – the big picture – so think about how you can summarise your most important points. Frequently questions have multiple parts, so it’s important to make sure you’ve answered every part. 2. Don’t write to the word count (at least, not initially)Self-editing as you write is difficult so I suggest you start by answering each question as fully as you can. Then you can go back and edit (and possibly re-edit) until you meet the word count. This helps you to concentrate on your key points and ensure that what you have written makes sense. In my experience, it’s also worth checking what constitutes a word – I have come across forms where everything from bullet points to dashes count towards the word total. If you’re in any doubt, do check with the funder. 3. Every word must earn its placeStaying with the challenges of the word count, aim for simplicity in your writing. Remove unnecessary words and consider restructuring sentences for clarity. Asking yourself ‘so what?’ in response to the statements you make can help you get to the heart of what you’re trying to convey. For more tips on editing down your written work, check out this excellent guide (with some cracking archaeology metaphors mixed in) by content writer Richard Berks. 4. Tell a compelling story…Some funders are specialists in your field and will understand the unique problems you exist to address. Many won’t be. Think about how you can help the funder to appreciate the issues. Explain what it’s like to be in the shoes of the people you support; consider whether you have space to include a short case study, or even a one-liner from someone you have helped. Remember, you’re communicating with a person (with emotions and empathy) rather than an organisation. 5. ...but avoid PR ‘puff’If you’re of the vintage that remembers the Ronseal adverts, you will know what I mean by taking a ‘does what it says on the tin’ approach. If not, it’s shorthand for accuracy, brevity and something being as effective as it claims to be, so evidence any bold statements you make in your applications and clarify points that could cause confusion. 6. Write for the audienceUnless they tell you otherwise, assume the reader knows very little about your organisation and approach. Keeping this in mind will help you decide what information to include and what supporting detail will be relevant. Mirroring the funder’s language can demonstrate that you are familiar with their work and have read their guidelines. 7. Keep the reader’s interestAs I explained earlier, grant assessors may read hundreds of applications every year, so think about how you can make yours more readable. I suggest avoiding jargon and internal shorthand (those descriptions we use that are meaningless to people outside our organisation), using quotes or bullet points to break up text, and varying sentence length and structure. That can be powerful. Impactful. Plus, if the format of the application allows, you could even add photos or graphics. 8. Check, check and check againAccurate spelling, grammar and punctuation demonstrates attention to detail. I like to print an application out in a different font and colour, then read it forwards and backwards to pick up errors. Because your brain anticipates what words are coming next, reading it from end to beginning helps you to pick up spelling mistakes, in particular. You can also use ‘read aloud’ software and listen to what you’ve written, rather than reading it. Finally, ask a colleague or friend – someone less familiar with the content - to read it for you. These tips should not only help to make your applications more compelling but might also mean they are more enjoyable to write. If you have tips you would add to this list, we would love to hear them. You can leave a comment below.

If you’re keen to sharpen up your application writing skills, check out our fundraising and bid writing training courses via the button below. INVOLVING FRONTLINE STAFF IN PLANNING YOUR FUNDRAISING STRATEGY - WHY BOTHER, AND HOW CAN YOU DO IT?9/10/2023 One of our main areas of work involves helping organisations to develop a new long-term fundraising strategy. Often the same question comes up early on when planning the process: who should we involve? For reasons that we've shared before, our process is very much not to sit in a room alone and write a fundraising strategy using a template. Instead we take a collaborative approach, facilitating a series of workshops to involve as many people as possible in the challenge of making fundraising more sustainable and successful. This involves mapping out key barriers and opportunities, developing clear strategic priorities, and identifying how the whole organisation can pull together better support good fundraising. So far, so good. But who should be involved in that process? Traditionally it’s the fundraiser(s) themselves, the senior management team, and representatives from the Board. All these people do indeed have a crucial role to play in making then enacting the key decisions. But if you stop there, you’re risking limiting your perspective, therefore creating a weaker fundraising strategy. The aim of this blog is to convince you that involving your frontline staff in developing your fundraising strategy is important. So what are the benefits?1. Frontline staff are closest to your service users, so can better articulate their views and needsDepending on the nature of your work, the people that you support – and their families – can be a real engine when it comes to raising money, advocating for your work, and opening crucial doors for fundraising. But how might they want to be involved? What are their concerns and barriers? And what do they need from you to feel equipped to play a role? Answering these questions will help you to plan fundraising activities and decide how to resource them. While it probably won't be practical to involve these people directly in your strategy process, your frontline staff do have a good relationship with them, so will know how best to gather, represent and respond to their needs and wishes. They'll certainly be better placed to this than your management, or even your fundraiser(s). 2. Frontline staff bring crucial insights about your workDeveloping a fundraising strategy in isolation of your service delivery means you’ll miss out on crucial "crossover" observations. For example, how well your services are performing – and how you’re collecting impact data – directly impacts your ability to secure grants. The activities that you run, and the spaces where you run them, can provide an untapped opportunity to raise money, recruit supporters and develop new earned income opportunities. It's easy for management and fundraising staff to make assumptions about what your key opportunities and barriers are. But if these assumptions are wrong, you’ll make the wrong decisions, and invest time and money in the wrong areas. Again, your frontline staff can provide essential insight. 3. If frontline staff are involved in planning your strategy, they’ll be better advocates and ambassadors for your fundraisingWe all struggle to get on board with a strategy that we haven’t contributed to or been asked about. It’s just an abstract document that, at best, we read then forget about. But when people are involved in the process and can understand your decision-making, and the need for better fundraising to safeguard the future of your organisation, they’ll be naturally more engaged in making it a reality. I’ve seen it so often - a CEO says that frontline staff won’t want to be involved in the fundraising strategy, won’t have anything to say, won’t have time to contribute. But when you involve them, they’re enthusiastic about being able to share their perspective, buy into what you’re trying to achieve, and become more motivated about their own role (even if it’s a small one) in making your fundraising more successful. But how can you realistically involve frontline staff in your fundraising strategy process, when they don't have any time to spare?1. During your first strategic planning sessionOur strategic planning workshops always follow a similar pattern: the first session(s) focuses on “discovery” – with everyone getting all their ideas, observations and concerns out in the open, then the later session(s) are dedicated to decision-making using that information. While your frontline delivery staff may very well not have the time or appetite to participate in the full process, asking a few representatives to come along to the first workshop – even just for the first couple of hours – may be a handy compromise approach, to ensure their views are factored into your thinking. 2. Requesting their views via their line managerWe’ve worked with organisations who have gained really helpful insights by asking their Service Manager(s) to coordinate gathering feedback and ideas from their own particular team. This can be done during regular team meetings, one-to-one conversations or a dedicated short workshop session. Managers can then collate feedback and share a summary with whoever is leading the fundraising strategy process. While this approach may only capture a few headline ideas, it’s a helpful light-touch option where frontline staff are stretched to capacity already. 3. Creating an online surveySimilarly, you can collect brief feedback by asking frontline staff to complete a five-minute survey. I’ve seen organisations gather surprisingly helpful insights by asking just a handful of carefully-worded questions, such as “What is the biggest thing that holds back our fundraising?” or “What do you think is our biggest missed opportunity with fundraising?” While it'll require a few reminders to ensure enough responses, it’s worth the effort. Even a single-page summary of collated ideas can be a valuable input into your fundraising strategy process. It’s easy to skip gathering input from frontline staff, assuming they lack either the time or knowledge to help. But finding ways to involve them in the initial stages of a fundraising strategy process will help you to gather invaluable ideas and perspectives, and ultimately develop a more successful and achievable fundraising strategy.

By the way, while we've focused on fundraising in this blog, many of the same principles apply for an organisational strategy too. We’ve facilitated fundraising strategy workshops and consultation processes for hundreds of charities and social enterprises. If you think we could help you, don’t hesitate to get in touch. It’s been eight years since we started providing trusts fundraising support to charities and social enterprises, alongside our strategy work. In that time, we're thrilled to have raised millions of pounds in grant funding. We've had projects that have been a huge success, and projects that haven’t quite gone to plan. We’ve learned loads about what it takes to secure funding in a hugely competitive landscape, and what we need from an organisation to our job well. Summer usually provides a rare opportunity for some down time to step back and gain perspective - whether that's while having a long walk in the sunshine (lesser spotted in 2023) or bobbing around in the sea on holiday (my personal favourite). So, this summer, we're reflecting on our top tips on how charities and social enterprises can work best with a consultant - whether that’s us or someone else. These tips are focused on trusts fundraising, but many of the general principles apply to other types of fundraising too. 1. Be clear why you need consultancy support in the first place - is it capacity, expertise, or both?It sounds obvious, but a consultant or freelance fundraiser can provide different things - they might bring valuable expertise or perspective that you don’t have in-house, or they might primarily provide extra 'hands-on' capacity at a time when, for whatever reason, you don’t have a staff member who can lead on the work. Our work with charities and social enterprises can take many different forms. For example:

Asking yourself what you actually need - and how it fits with your existing capacity and expertise - will guide how long you need support for, the rate you should pay, and the exit strategy you’re working towards (see below). It may well save you money, if you realise that you only need expertise to help you with a very specific piece of work, or short-term support to address a capacity gap. 2. Understand - and provide - what we need to do a good jobWhen working with an organisation, particularly longer-term, it's so helpful to be able to roll your sleeves up and really immerse yourself in their work and previous trusts fundraising efforts. It's vital that we can spend time looking through project summaries, budgets, impact reports, previous funding applications, complete records of all submitted applications (successful and unsuccessful) and end-of-grant reports. This helps us piece together an organisation's strengths, weaknesses to address, and key opportunities to focus on. If we're missing information, we won't know key questions that we need to ask, and risk duplicating work that you've done previously. When you start working with a consultant, give them online shared access to as much relevant information as possible, and ask them what they particularly need to do a good job, and how far back in time it's helpful to go. If necessary, you can always redact sensitive information or ask them to sign a specific non-disclosure agreement. 3. Keep us updated on key developmentsSharing information at the start of a project is important, but inevitably your plans will change as time goes by. For example, winning or losing statutory funding can have a key budgetary impact, service user feedback may change how you intend to deliver a project, unexpected developments might bump a capital funding need way up the priority list, or meeting a funder at an event may open up a big new opportunity. As external consultants, we may not be regularly involved in staff meetings - particularly if we’re working remotely - so it can be easy to forget to pass on important news to us. That's a missed opportunity, because we'll often be able to offer advice or adjust our approach in response. 4. Trust our judgement, but give us guidelines and even red linesSpecialist trusts fundraising consultants bring expertise on how to 'package' a project, present information in a budget and phrase things in applications. It's very likely that our approach will be different to your own, and may initially make you feel uncertain or even uncomfortable. If you're paying for specialist expertise, you should avoid undermining that investment by micro-managing the work or shutting down new approaches. We've previously worked with organisations where unfortunately applications became vastly more time-consuming to write, not to mention weaker, because of well-intentioned meddling. As a result, we raised less money. However, that’s not to say you should give a consultant complete freedom, particularly if it compromises your ethics and values - for example the way you portray your service users, use photos in applications, or who you're willing to seek funding from. I'd recommend having an honest and open conversation about this at the start, being clear about any “red lines” that mustn't be crossed, and sharing written information about your values and ethical fundraising policy if you have it. As well as reassuring you, this will also give your consultant confidence and freedom to work within those limitations. 5. Always keep oversight and ownership of our workOne basic principle of good consultancy is to ensure that the organisation receiving support is in a better position by the end than they were at the start. Yet this isn't always the reality - we’ve seen organisations end up in a real mess when a previous consultant walks out the door, losing access to application content, records of applications submitted and even key contacts at funders. This is why you should always ensure that you “own” - and have continuous access to - all the content and information produced on your behalf. Agreeing a regular meeting cycle, including key information to be provided in updates, also helps. A good consultant should appreciate the importance of this - for example, we always like to make sure we’re working out of a shared Google Drive or Dropbox folder, and encourage organisations to check files regularly and ask questions or voice concerns at any point. Try to have a clear exit strategy in mind, for example, aiming to recruit and hand over the work to a staff member after 12 months. When are you expecting your relationship with a consultant to come to an end, and what do you need to know, have and feel confident about by this point? 6. Ensure you remain front and centre with fundersAs well as owning your information, it's equally important to own your relationships with funders - they are funding you, not a consultant, and investing time in strengthening these relationships will help you raise more money in the long run. When working with a charity, we'll always encourage you to take the lead on making introductory calls or attending meetings with funders. We'll tend to work in the background - briefing you on what you might want to ask or tell a funder, and supporting at meetings when requested - not because we don’t enjoy speaking to funders ourselves, but because we think that (with support) you’re the best ambassador and advocate for your work, and the right person to build that relationship. This ensures there's no disruption whenever you're ready to move on from working with us. If you're speaking to a consultant who boasts about having brilliant relationships with funders themselves, always query how this has come about, and check that it's not at the expense of the grantee organisation being front and centre. Are you a consultant or charity / social enterprise with your own tips on making things work well? Share your ideas in the comments below.

One of the topics that I currently find myself talking about frequently - when working with organisations on funding bids or delivering trusts & foundations training - is the need to differentiate your work and avoid the perception of duplication. Why is differentiation so important when applying to trusts & foundations?This isn’t a new issue, but is perhaps more important than ever. With such high demand for funding, and trusts & foundations so overstretched, one of the ways that funders can maximise their impact is by being really careful and strategic about not funding very similar organisations or overlapping services. From their perspective, if one organisation does something well already, where’s the benefit (or at least urgency) in funding another organisation to do it too? Often, this is an explicit decision-making criterion for funders. They will assess your application not simply based on the quality and impact of your own work, but in the context of how many similar services exist - or they have recently funded - in any given cause area or geographical area. I've seen this frequently cited in feedback given by the National Lottery Community Fund, for instance. While this makes sense, the issue is whether a funder's perception of the similarity of your work to others is really accurate. The last thing you want is to see a key application rejected because there are some key differences and nuances in your work that you haven’t explained properly. So differentiating your work is important. And in a more general sense, being able to clearly and confidently explain your place in the local landscape - in terms of which service gaps you meet, and who you partner with or take referrals from - will always inspire confidence. This will not only increase your chances of securing funding, but also help funders to learn more about the complexities on the ground in your area of work. Being different doesn't mean being unique, or better than other organisations working in a similar spaceFirstly, differentiation doesn’t mean being absolutely unique. Nobody realistically expects you to be the only employability service in Lancashire, the only organisation educating young people about climate change etc. What’s important is demonstrating why your service or approach is more accessible, more appropriate and more impactful for the specific people that you support. This isn’t about trash talking what other organisations do. There may be perfectly good reasons why your user group would face additional needs and barriers when trying to access more generalist support offered by another organisation, or a specialist service set up for people in a different situation. To give some examples from my own previous work, there may be a clear need for:

With all the above projects, there’s a risk that a funder could incorrectly perceive them as being surplus to requirements, or already covered by existing service provision. But a compelling case for support - clearly explaining how you're different and situating your work within the existing landscape - will significantly increase your chances of securing funding. Building your case for support: how can you demonstrate that your work is different and urgently needed?Firstly, it helps to have a curious and critical mindset. Put yourself in the shoes of a funder with no prior knowledge of your work and ask how they might perceive it. Why do you deliver activities in a certain way? What other services could the people you support choose to access? And why aren’t those services accessible or appropriate for their needs? Once you've asked the right questions, seek out convincing evidence of how your work is different: Centre the perspective of the people you support. Make liberal use of testimonials, case studies and survey data from your service users. Enabling them to talk about their own experiences, needs and barriers - and the value they see in your work - in their own voice will always be more powerful and compelling. Draw on your own lived experience. Did you establish your organisation in response to a specific unmet need, or to prevent others from going through the same experience as you? Do your senior leaders, project staff or volunteers have lived experience that enables them to intuitively understand and address the gaps in local service provision? Describe what is happening on the ground in your area. Did your local authority previously provide more accessible support that has been lost in recent cutbacks? Has the closure of another charity impacted the needs of the people you support? Has another organisation approached you to address a need they know they can’t meet? Describe the evolution of your own work. Perhaps you've learned through experience that a different type of service is needed. Can you show how previous feedback and evaluation data has enabled you to hone and improve your work over time, and become more collaborative with other local services (e.g. through referral pathways, strategic partnership working)? Cite independent research. You might be absolutely convinced that your work is different, but do you have third party evidence to back it up? Look for independent studies or local data that highlight gaps in local service provision, or examples of other organisations working in a different region that have successfully achieved impact by tackling a similar issue or gap. In conclusion...Remember that your work doesn’t need to be completely unique or mind-blowingly innovative to be different and valuable. But don't take it for granted that a funder will understand that - you need to build a compelling case for support that clearly explains why your work is vital for your own particular service users.

In a world where funding is ultra-competitive, spending time carefully situating your work within the wider delivery landscape - and avoid perceptions of duplication - is an investment well worth making. Our consultant Charlotte Chilvers shares her tips below on how small charities and social enterprises can increase their income from social media. Before joining Lime Green, Charlotte used to deliver social media training for small charities for Macc, Manchester’s voluntary sector infrastructure support organisation. With statutory and trusts funding becoming even more competitive post-pandemic and with the current cost-of-living headache, you may be revisiting your fundraising strategy and considering where else to find pots of money. Social media may seem to be an ambiguous source of income, but with over 84% of the UK population actively using social media, many organisations have found it to be a successful tool for fundraising. Although you’ll need to input some time (another precious resource) to research which methods would work best for your organisation, we’ve done some of the legwork for you below... First up, what can social media do over grant funding?Ignoring the endless number of cat videos, social media has some clear advantages over income from statutory or trusts & foundations funding: It's unrestricted income - this should light up pound signs in your eyes immediately. However your fundraising strategy incorporates social media, one of the clear benefits is that in most cases, the money raised is unrestricted and can be spread across your organisation’s projects and overheads. Despite a recent shift in that direction from some funders, grant funding is still rarely unrestricted. It’s a free resource - we’ll start with a caveat. Yes, you will need someone to set up social media accounts and manage them, which may be a paid staff member. However, with a bit of time and input at the start, such as establishing a social media strategy, and utilising free scheduling tools such as TweetDeck and Buffer, your online fundraising can build up nicely. Alongside this, you’re easily able to raise awareness and promote activities and events. Social media can support your grant applications - your content can help tell the story of your organisation, service users, and donors. Comments on your posts and events can also contribute to your grant applications - feedback from diverse networks (e.g. service users, community members, donors) are perfect for monitoring and evaluation and building your case for support. Now that’s swayed you, how can you fundraise on different social media platforms?One of the key benefits for not-for-profits is their ‘Fundraisers and donations’ dedicated section for charities looking to raise income through public donations. Whilst success can vary, organisations have been able to generate income through promoting events and ticket sales, ‘birthday appeal’ donations from users, sharing direct links to Fundraising pages, as well as launching poll-voting for donations (similar to community supermarket tokens). This can be done by a simple personal account in the organisation’s name, or by a ‘business page’ which gives a greater breakdown of traffic and interaction with your posts. The beauty of social media means your posts and activity promote your organisation and raise awareness, whilst requests for donations can then be shared by other online users. This external virality opens up opportunities for income from a wider audience, allowing you to (hopefully) sit back and see some pounds coming in with little time and effort. Alongside this, there are no limitations on character counts, which means you can really show off what your organisation does through storytelling and demonstrating your evidence of need. Funders will often request your social media links, so it’s worth very clearly demonstrating this through your account through photos, short videos, infographics, blogs, articles, events, etc. Depending on your privacy settings, publicly available posts can also be used for gathering data/quotes for impact. Top Tip: Go with the trends: so many viral fundraising activities have grown from Facebook (17 million posted an ‘Ice bucket challenge’ video in 2014 alone) so direct your fundraising posts to relevant trends, use hashtags, and share widely! Instagram: Unlike Facebook, Instagram pages need to be highly visual - content is primarily made up of photos and videos. In terms of generating income, like Facebook, there is the option to set up a business account to sell tickets, items, merchandise, and other products, as well as link to your fundraising page. As part of Zuckerberg’s Meta world, Instagram also has a non-profit fundraisers section, which outlines how best to maximise donations. For example, utilising hashtags, adding links to 24-hour ‘stories’, and live-streaming either from your organisation or from donors. Lastly, the group fundraiser option is a brilliant way to collaborate and raise money with people you may already be connected to, such as public figures and people who have successfully raised funds for you before. Due to the visual nature, Instagram is a great way to show off what you do and connect people with your work. This also offers a different route to storytelling. For example, live streaming videos during events, service user/staff/volunteer "takeovers" to show how your organisation benefits them, infographics with quotes, and photo/video posts all provide a very clear impression of what you do, and why users should donate. Top tip: Make your fundraising request post visually appealing, headline it with a catchy title, and use compelling images to show the impact of people’s donations. Twitter Twitter posts are limited to 280 characters, meaning you’ll need to be creative in how to fit information in short tweets and threads. This means your message or donation request has to be clear and to the point. Tweeting your donation links can build up momentum to your organisation’s fundraising needs, particularly when utilising hashtags and tagging relevant organisations/people/pages to start campaigns or conversations. Twitter is a brilliant way to connect, influence and build networks locally and nationally with other organisations, funders, local councillors etc. Your content can be easily shared through retweets, hopefully widening your reach to more potential donors. With Elon Musk's Twitter takeover, many organisations are reviewing their own standpoint on Twitter, as well as considering alternative platforms. If that's you too, here are a couple of articles by Charity Digital to help: Should charities stay on Elon Musk's Twitter? | Exploring the alternatives to Twitter Top tip: Keep your message brief but comprehensive, and use Bitly to keep your website links short and within the character limit! TikTok Look no further than our podcast episode with the brilliant Nana Crawford, talking about how the British Red Cross was one of the first charities to successfully start fundraising on TikTok, and how they made it work. This all sounds great, but how do I get started?

|

Like this blog? If so then please...

Categories

All

Archive

May 2024

|

Lime Green Consulting is the trading name of Lime Green Consulting & Training Ltd (registered company number 12056332)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed